>Corresponding Author : Bendahou H

>Article Type : Case Report

>Volume : 2 | Issue : 3

>Received Date : 01 Aug, 2022

>Accepted Date : 10 Aug, 2022

>Published Date : 13 Aug, 2022

>DOI : https://doi.org/10.54289/JCRMH2200116

>Citation : Bendahou H, Abouriche A, Selmaoui M, Haboub M, Arous S, et al. (2022) Painless Aortic Dissection Revealed After its Rupture to the Pericardium: About a Case and Review of the Literature. J Case Rep Med Hist 2(3): doi https://doi.org/10.54289/JCRMH2200116

>Copyright : © 2022 Kritika, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Case Report | Open Access

1Doctor, Cardiology Department, Hospital university of Casablanca

2Professor, Department of Cardiology, Hospital university of Casablanca

*Corresponding author: Bendahou H, Doctor, Cardiology Department, Hospital university of Casablanca

Abstract

Stanford type A aortic dissection is a rapidly evolving pathological process often with poor prognosis if no urgent surgical management. However, it may be asymptomatic in the acute phase with late symptomatic presentation or incidental diagnosis on chest imaging. We report the case of a 52-year-old man in whom a painless aortic dissection was discovered incidentally following a pericardial effusion assessment. The patient's condition was successfully managed with uneventful open heart surgery. This case demonstrates an extremely rare presentation of accidental hemorrhagic pericardial effusion caused by painless aortic dissection.

Abbreviations: TEVAR: Thoracic Aortic Endovascular Repair

Case report

This is Mr. S.B, 52 years old, chronic smoker, followed for balanced arterial hypertension for 5 years under medical treatment, and without any other particular pathological history, presenting for a mild dyspnea.

On clinical examination, we note an asymptomatic patient, without chest pain, in good general condition, with a blood presure = 135/85 mmHg, and a heart rate = 82 bpm, without signs of heart failure.

On the electrocardiogram, there is a regular sinus rhythm at 80 bpm, with no conduction or rhythm abnormality (Figure 1).

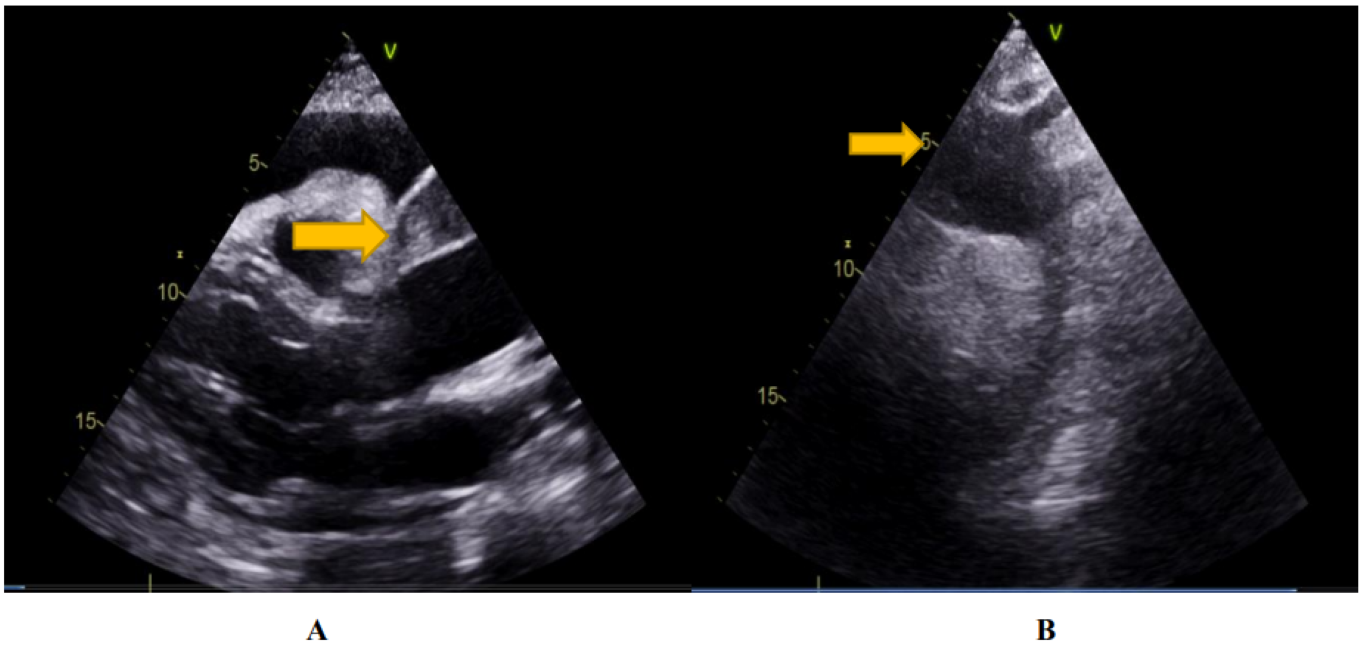

An echocardiography performed on admission shows moderately abundant pericardial effusion, predominantly posterior with: 14 mm next to the OD, 12 mm next to the RV, and 30 mm next to the LV, with good biventricular function, LVEF at 60%, with no variation in inspiratory flow, and a slightly dilated inferior vena cava at 21mm and not very compliant (Figure 2).

Also note a dilatation of the ascending thoracic aorta to 51 mm, with strong suspicion of aortic dissection. The aortic valve was normal and without leakage or stenosis.

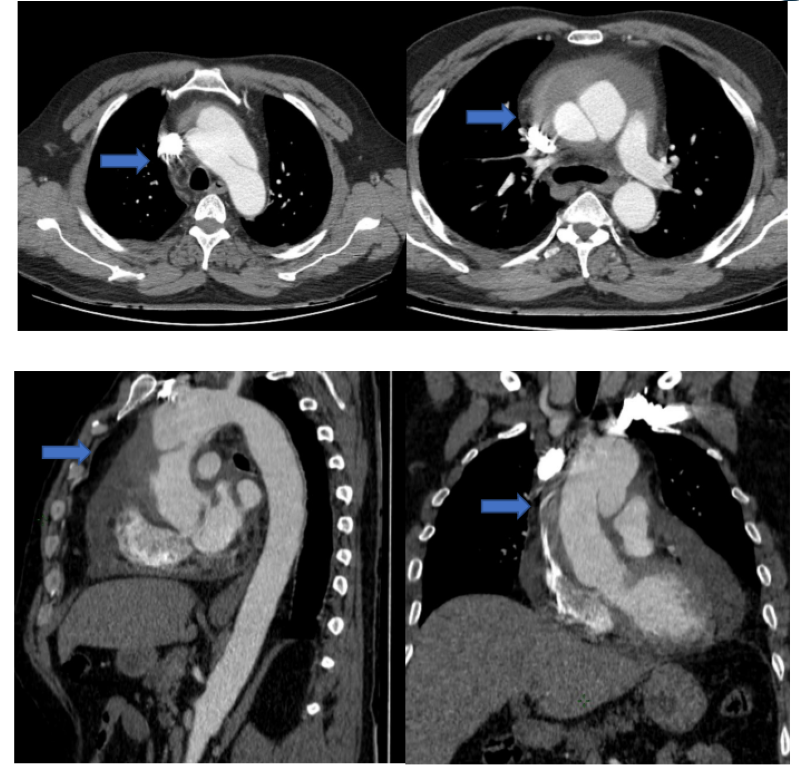

For this, a thoracic CT angiography was requested confirming a type A aortic dissection of the STANFORD classification, of the ascending aorta extending to the aortic arch, associated with a parietal hematoma (Figures 3).

A complete biological assessment was carried out returning normal, without notable anomaly.

The patient was urgently sent to the operating room of the cardiovascular surgery department, where the ascending aorta was replaced by a DACRON prosthetic segment. The surgical procedure was uneventful, with good postoperative evolution.

Figure 1: Normal ECG

Figure 2: dissection of the ascending aorta (yellow arrow) on the major axis parasternal view (A) and the suprasternal view (B). Aspect of the coagulated pericardial effusion, on the long axis parasternal section (A).

Figure 3: Appearance of aortic dissection type A of the STANFORD classification (blue arrow), extending from the ascending aorta to the aortic arch, associated with a parietal hematoma.

Discussion

An aortic aneurysm is a localized dilation of the aorta. It can affect the different segments of the aorta: the aortic root, the ascending aorta, the aortic arch or the descending aorta.

In a study [3], 60% of thoracic aneurysms involve the aortic root or the ascending aorta, and 40% involve the descending aorta.

10% involve the arch and 10% involve the thoraco-abdominal aorta, with some involving more than one segment [2].

The natural course of thoracic aneurysms in particular is a progressive extension, with an increase in pressure on the wall of the aneurysm and thus an eventual rupture, which is called a dissection [2,3].

The most important predisposing factor for acute aortic dissection is systemic hypertension. But there are other predisposing factors including collagen disorders such as Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and annuloaortic ectasia. Bicuspid aortic valve, aortic coarctation, Turner syndrome, coronary artery bypass surgery, previous aortic valve replacement may very rarely be predisposing factors [2,4].

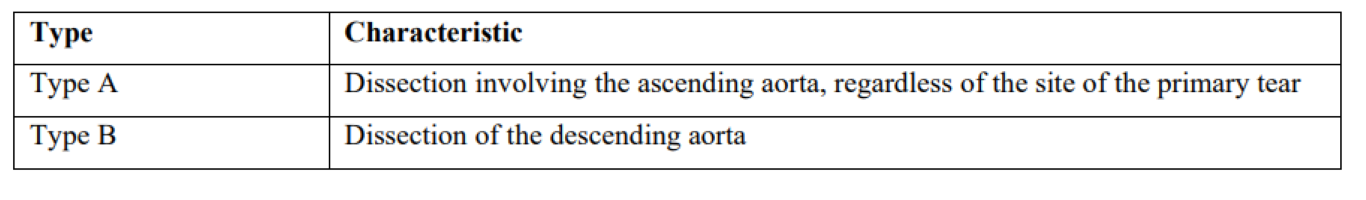

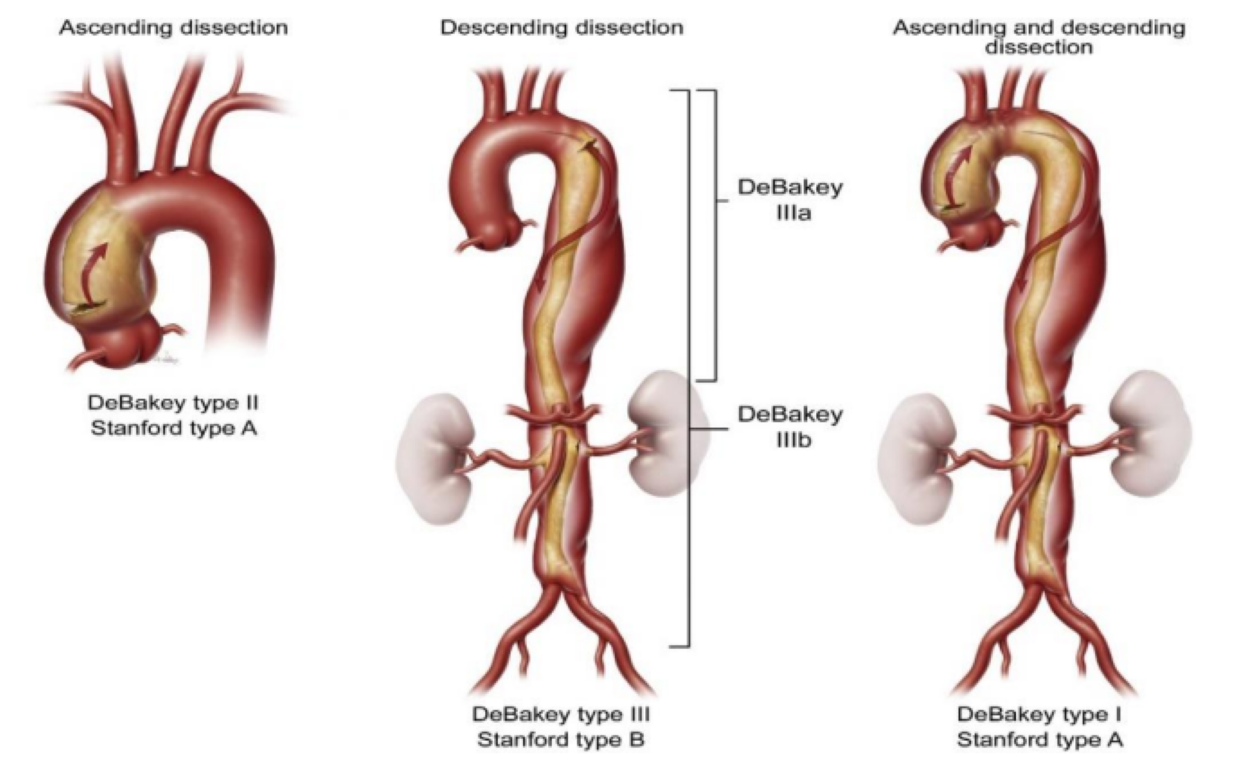

There are two classifications of dissections: Stanford (Table 1) and DeBakey (Table 2).

Stanford Type A includes dissections that involve the ascending thoracic aorta, while Type B dissections do not involve the ascending thoracic aorta.

The DeBakey classification of type 1 concerns the entire aorta, type 2 dissections concern the ascending aorta and type 3 dissections concern the descending aorta. Thus, Stanford Type A dissection includes DeBakey Types 1 and 2, and Stanford Type B is equivalent to DeBakey Type 3 (Figure 4) [2].

Table 1: Stanford classification

Table 2: DeBakey classification

Figure 4: Stanford and DeBakey classifications of aortic dissection [5].

The diagnosis of aortic dissection is usually suspected in the presence of severe back pain, abrupt onset, tearing if it is a distal dissection of the descending artery or anterior chest pain if it is an ascending aortic dissection [2].

Painless dissection has been reported, but is relatively rare. In an analysis of 977 patients from the International Acute Aortic Dissection Registry 3, only 63 patients (6.4%) had no pain [2].

However, so-called chronic type A aortic dissections represent a different category of patients presenting with atypical symptoms related to enlargement of the dissection, malperfusion (decreased visual acuity, pain in the extremities of the limbs or syncope), to valvular disease (dyspnea, edema of the lower limbs), or even asymptomatic at the start of the dissection, which prevents an early diagnosis [6]. As is the case of our patient.

For this, a careful history is necessary to determine the symptoms announcing the beginning of a dissection [6].

And if there is any suspicion, the diagnosis must be confirmed by other specific imaging modalities, including transesophageal echocardiography, chest CT angiography or magnetic resonance angiography. And among the most evocative signs of the chronic picture of the dissection we find: a thick and immobile intimal flap, an aneurysmal dilation of the thoracic aorta or the presence of a thrombus in the false channel [6,7].

Pericardial effusion is a common complication of Acute Type A Aortic Dissection, and generally occurs by two mechanisms. The first and most common is the transudation of fluid through the thin wall of the false channel into the pericardial cavity. Second, and it is less common, the dissected aorta can rupture directly into the pericardial space with subsequent tamponade [8]. The pericardial effusion can coagulate as it did in our patient.

Cardiac tamponade is diagnosed in 8 to 10% of patients with acute type A aortic dissection, often painless, and represents a predictive factor for poor prognosis, and the leading cause of death [8].

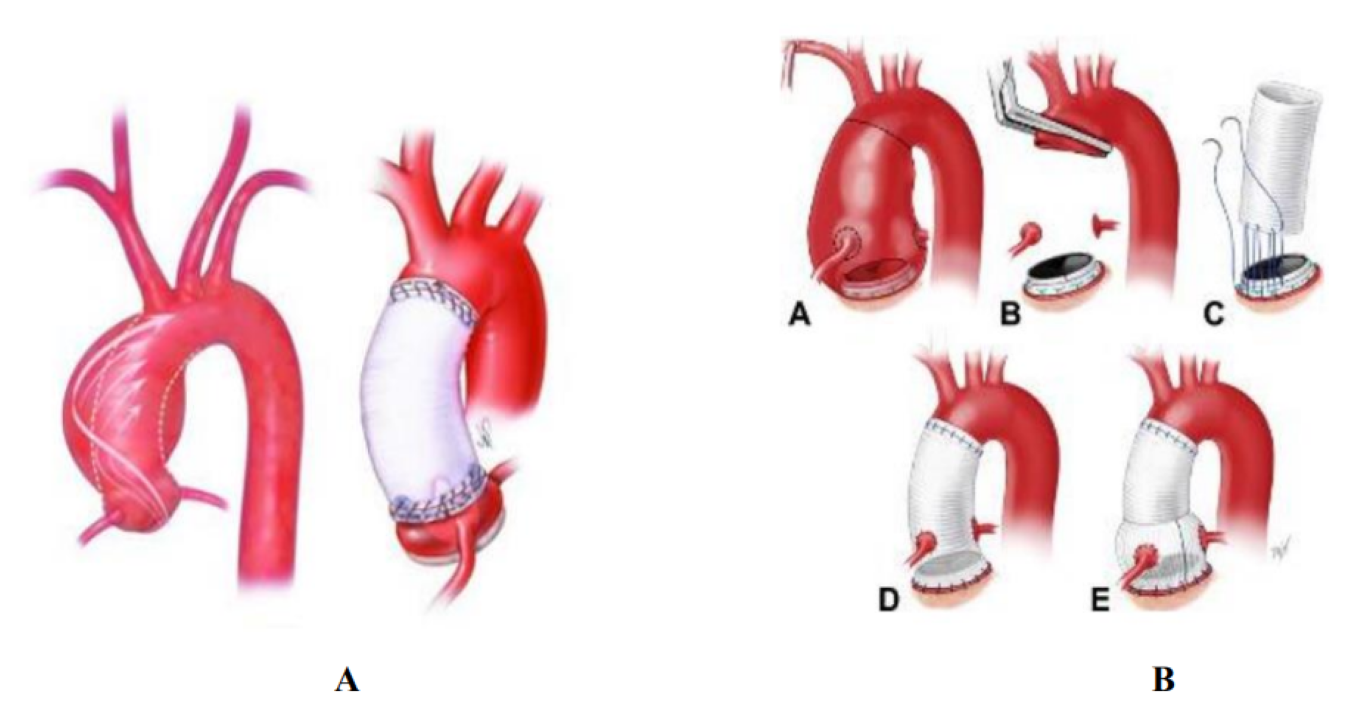

Regarding the therapeutic management, for type A dissection, the aim of the treatment is essentially the repair of the dissected aorta, taking into account the comorbidities of the patients. Endovascular treatment can be performed in patients unsuitable for open-heart open surgical repair [9].

Depending on the extent of the dissection, open-heart surgery remains the right alternative, and may include simple replacement of the ascending aorta with a supracoronary tube (DACRON tube, Figure 5, A) [9], or even the BENTALL technique (Figure 5, B) if severe aortic insufficiency or destruction of the aortic valve is associated.

The technique of reimplantation of the aortic valve according to Tyrone-David: is an alternative also can be carried out.

Figure 5: A, Replacement of the ascending aorta by supracoronary tube, DACRON tube. B, BENTALL technique.

Chronic lesions limited to the ascending aorta that do not involve the aortic arch, aortic valve, or coronary arteries, can be repaired with endovascular stents, as a variant of thoracic aortic endovascular repair (TEVAR) [10], but studies are still very limited in this context, and publications are limited to clinical cases.

Data on outcomes of surgery in patients with chronic type A dissection on dissected native ascending aorta are limited to case reports [9]. But more often than not, the results of these surgeries are favorable.

In a study carried out on the operative risk, hospital mortality was lower in patients with stable or so-called chronic aortic dissection. Of the 67 operated patients, no intraoperative deaths and 3 early perioperative deaths [9].

Conclusion

Chronic type A aortic dissection is a difficult diagnosis with a wide range of clinical presentations, including asymptomatic presentation or discovered following accidental hemorrhagic pericardial effusion. Pericardial puncture in this context is prohibited [6]. Therefore, it is strongly recommended to obtain a computed tomography of the chest before any diagnostic pericardial puncture. Surgical repair is the treatment of choice for chronic complicated Stanford type A aortic dissections.

Replacement of all dissected aortic tissue and repair or replacement of the aortic valve can be done safely in the majority of patients with chronic type A dissection [9].

Bibliographie

- Nienaber CA. (2007) Pathophysiology of acute aortic syndromes. In: Baliga RR, Nienaber CA, Isselbacher EM, Eagle KA. Aortic Dissection and Related Syndromes. New York: Springer. 17-43. [Ref.]

- Conor F, Hynes, et al. (2016) Chronic Type A Aortic Dissection Two Cases and a Review of Current Management Strategies. AORTA. 4(1): 16-21. [Ref.]

- Tsai TT, Evangelista A, Nienaber CA, et al. (2006) Long-term survival in patients presenting with type A acute aortic dissection: Insights from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD). Circulation. 114(1 Suppl): I350-1356. [PubMed.]

- Larson EW, Edwards WD. (1984) Risk factors for aortic dissection: A necropsy study of 161 cases. Am J Cardiol. 53: 849-855. [PubMed.]

- Hong JC, Huu AL, Preventza O. (2021) Medical or endovascular management of acute type B aortic dissection The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. S0022-5223(21)00733-9. [PubMed.]

- Abugroun A, et al. (2019) Chronic Type A Aortic Dissection: Rare Presentation of Incidental Pericardial Effusion. Hindawi. Case Reports in Cardiology. [Ref.]

- Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al. (2014) 2014 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Aortic Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European Heart Journal. 35(41): 2873-2926. [PubMed.]

- Hiratzka LF, Bakris GL, Beckman JA, et al. (2010) 2010 ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic disease. A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Radiology, American Stroke Association, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and Society for Vascular Medicine. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 121(13): e266-369. [PubMed.]

- Rylski B, et al. (2015) Outcomes of Surgery for Chronic Type A Aortic Dissection. Ann Thorac Surg. 99(1): 88-94. [Ref.]

- Hynes MD, et al. (2016) Chronic Type A Aortic Dissection Two Cases and a Review of Current Management Strategies Conor F. AORTA. 4(1): 16-21. [Ref.]