>Corresponding Author : Musleh Mubarki

>Article Type : Case Report

>Volume : 2 | Issue : 4

>Received Date : 18 Aug, 2022

>Accepted Date : 29 Aug, 2022

>Published Date : 01 Sep, 2022

>DOI : https://doi.org/10.54289/JCRMH2200121

>Citation : Mubarki M, Alahmari M, Alahmari A, Kadasah S, Asiry AJ, et al. (2022) Nasopharyngeal Cancer in Childhood, Case report. J Case Rep Med Hist 2(4): doi https://doi.org/10.54289/JCRMH2200121

>Copyright : © 2022 Mubarki M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Case Report | Open Access

1Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head & Neck Surgery, Aseer central hospital, Aseer Region, Saudi Arabia

2Department of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery armed forces hospital of south region, Saudi Arabia

3Collage of medicine, King Khalid University, Aseer Region, Saudi Arabia

*Corresponding author:

Musleh Mubarki, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head & Neck Surgery, Aseer central hospital, Aseer Region, Saudi Arabia

Mohammed Alahmari, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head & Neck Surgery, Aseer central hospital, Aseer Region, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is the most frequent cancer that begins in the nasopharynx and spreads to the head and neck in adults. In individuals with nasopharyngeal cancer, the outcome after medical intervention can be relatively excellent if they receive adequate and effective treatment. NPC, on the other hand, is extremely rare in childhood, and its prevalence rises with patient age. In general, NPC has a more aggressive character, with frequent distant metastases during the early stages of the disease in childhood.

Keywords: Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma; Childhood; Head and Neck Cancer

Abbreviations: NPC: Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma, CT: Computerized Tomography, EBV: Epstein-Barr Virus, PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction, WHO: World Health Organization, SEER: Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Outcomes, OS: Overall Survival

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a cancer that develops from the epithelial cells that line the nasopharynx's surface. It's a common head and neck tumor in adults, and the prevalence varies a lot depending on region. Regions including as Southern China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan have been identified as high-risk areas for NPC. NPC, on the other hand, is extremely unusual in children, regardless of geography [1]. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is for 1-5% of all pediatric malignancies and 20-50% of all primary malignant nasopharyngeal tumors in children [2,3], In children, the median age of nasopharyngeal occurrence is 13 years, with black boys having a higher frequency, Nasopharyngeal cancer usually starts in the lateral wall of the nasopharynx, which includes the Rosenmuller fossa, and extends into or outside of the nasopharynx, up to the contralateral wall, or in a posterosuperior orientation up to the cranial base or palate, nasal cavity, or oropharynx [4]. Cervical lymph nodes are frequently affected by metastasis [5]. The internal jugular chain, accessory spinal chain, and retropharyngeal space all have a lot of lymphatic drainage. The standard therapy for children with NPC has mostly followed the adult guidelines.

Case Report

Our case is 14 years old Saudi male medically free and without any previous surgical intervention, came to authors' clinic complaining of bilateral nasal obstruction and mouth breathing with snoring during sleep. No prior history of nasal bleeding or discharge, no history visible or palpable head or neck swelling, no current symptoms of fever, weight loss, ear fullness or decreased hearing. On examination, patient was alert and vitally stable, nasal examination showed a normal overlying skin, nasal mucosa and septum, without any signs of bleeding, discharge, ulceration or obvious mass. no visible external or internal nasal deformity except for bilateral hypertrophied turbinate.

On examination, normal head and neck finding without any visible or palpable swelling, deformities, or evidence of cranial nerves pathology. Grade III palatine tonsil but without any atypical other oral finding. On otoscopic examination, there is no evident abnormalities regarding external ear, external auditory canal and tympanic membrane. Audiometry and tympanometry showed a bilateral preserved hearing function. Fibroscopic examination of the upper respiratory tract showed a large purplish nasopharyngeal mass more on the right side of nasopharyngeal vault, soft consistency with regular shape, smooth surface lobulated and partially obstructs the right choanae, well defined edges, with a scattered spots of hypervascularity, no visible current bleeding

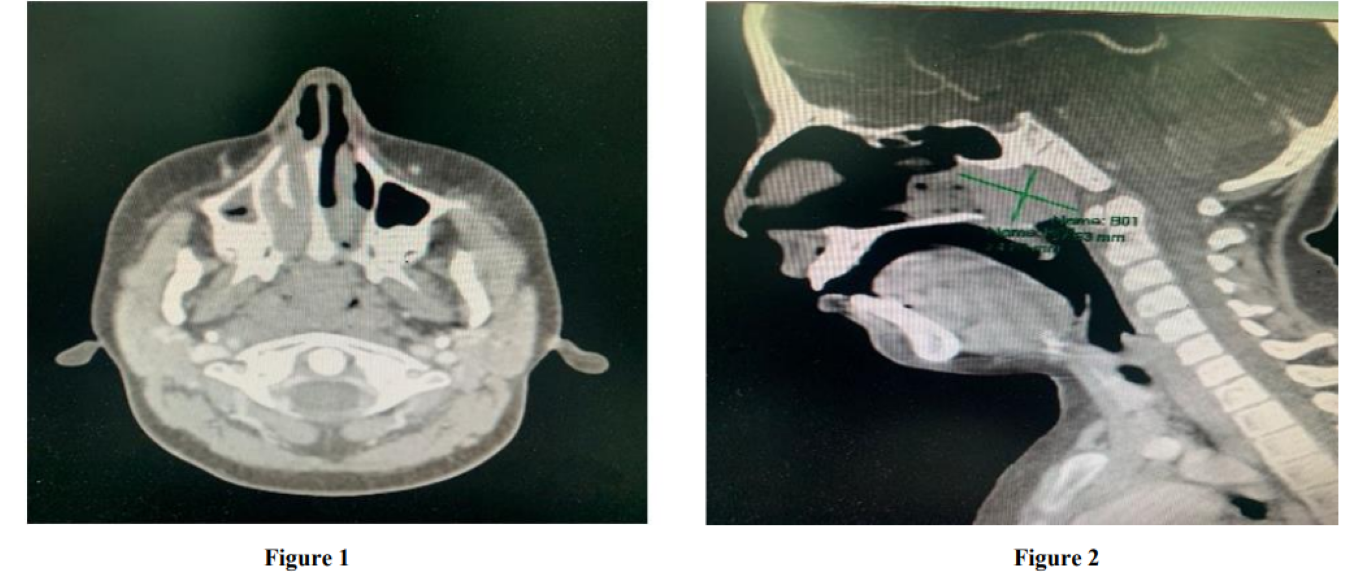

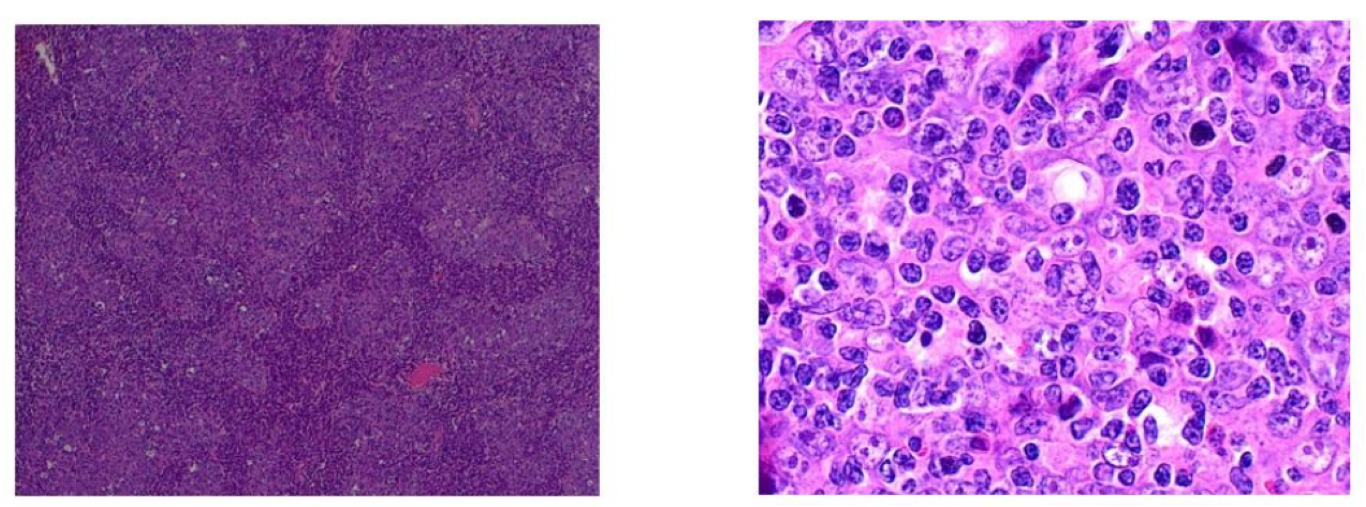

A computerized tomography (CT) scan of the neck demonstrate a 24x37 mm mild enhancement mass that occupied the right nasopharyngeal cavum space extended to the right posterior nasal cavity causing nasal airway narrowing as well as nasopharynx (Figure 1,2). After that patient preparing for nasopharyngeal mass biopsy that revealed poorly differentiated carcinoma (Figure 3,4), and immunohistochemistry showed positivity for HLA DR, CK19, and EMA, without reactivity for CK7 and CK20 compatible nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) panel and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were requested but both were negative.

Discussion

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is the most common type of nasopharyngeal tumor. This difficult disease has a complex etiology that includes virological, environmental, and genetic components. The incidence of nasopharyngeal cancer varies greatly depending on region. In general, the risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma rises with age, peaking at 50-59 years of age in some populations, with a slight peak in late infancy in others [6]. Nosebleeds, nasal congestion and obstruction, or otitis media are common symptoms of nasopharyngeal cancer. Because the nasopharynx has a lot of lymphatic outflows, bilateral cervical lymphadenopathies are frequently the initial symptom of illness. The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes three histological subtypes: include keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma (type 1), non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma (type 2), and undifferentiated carcinoma (type 3), The Epstein-Barr virus infection of cancerous cells is significantly linked to type 3 nasopharyngeal carcinoma, which has a high rate of distant metastases to the bones, lungs, and liver. Bone marrow metastasis, on the other hand, is a very uncommon illness that can have a significant impact on patient survival time [7]. From 1988 to 2006, researchers investigated the surveillance, epidemiology, and end outcomes (SEER) database for patients diagnosed with NPC. They compared the clinical characteristics and outcomes of 129 children and adolescents (Aged 20) with 5885 adults. Advanced stages were more frequently detected in younger patients (31% and 46 % of combined children and adolescents had stages III and IV, respectively), and % had WHO type III histology [8]. because there is a strong correlation between undifferentiated cancer histology and Epstein-Barr virus infection [9]. Because of its strong relationship with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, a higher percentage of undifferentiated histology, and a higher frequency of advanced locoregional illness, nasopharyngeal carcinoma in children is distinguished from the adult variant [10]. Despite the fact that adolescents and young people had a higher frequency of advanced loco-regional disease than older adults with nasopharyngeal cancer, the overall survival rates are not significantly different. Children and adolescent NPC patients have better outcomes than adult NPC patients, according to several studies, with 5-year overall survival (OS) rates of 71 percent vs. 58 percent, respectively (p = 0.03) [11]. The standard treatment for NPC in children has generally followed the adult guidelines. Due to the sensitivity of undifferentiated NPC to radiation, high-dose radiation to the nasopharynx and involved cervical nodal areas is the basis of locoregional NPC treatment. This medication, on the other hand, appears to manage the main tumor but has no effect on the appearance of distant metastases, Children with advanced NPC (Stages III and IV) who are treated with radiation therapy alone have a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of 20 to 40% [12]. Long-term survivors are especially concerned about high-dose radiotherapy-related morbidities in children, such as xerostomia, hearing loss, neck fibrosis, hypothyroidism, and the most concerning, a second primary tumor in the radiation area [13]. Unfortunately, typical chemotherapy combinations or treatment plans for pediatric nasopharyngeal cancer are not available due to the limited sample sizes. However, platinum-based chemotherapy, such as BEP (Bleomycin, Epirubicin, Cisplatin), PF (Cisplatin, Fluorouracil), MPF (Methotrexate, Cis.platin, Fluorouracil), and PMB (Methotrexate, Cisplatin, Fluorouracil), has gained popularity. When a mix of different chemotherapy regimens and radiotherapy is used, the survival rate is roughly 40-90 percent, according to data from various studies [14-17].

Figure 1,2: (CT done show opacification of nasopharyngeal are extended to right nasal cavity, mass about 2.4*3.7 cm with mild enhancement)

Figure 3,4: (histopathology report show: poor differentiated carcinoma)

Conclusion

Childhood nasopharyngeal carcinoma is uncommon, it is associated with a higher rate of advanced locoregional disease, which needs careful considerations of any nasopharyngeal mass should be investigated regardless the age group and on the basis of NPC biology, it is obvious that therapy of childhood NPC requires early administration of an effective chemotherapeutic agent.

Acknowledgment:

We would like to thank all otolaryngologist radiologist, OR teams, and histopathologist in aseer central hospital.

Funding: No Funding sources

Conflict of interest: None Declared

Ethical approval: The case report was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee

References

- Healy GB. (1980) Malignant tumors of the head and neck in children: diagnosis and treatment. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 13(3): 483-488. [PubMed.]

- Deutsch M, Mercado Jr R, Parsons JA. (1978) Cancer of the nasopharynx in children. Cancer. 41(3): 1128-1133. [PubMed.]

- Ingersoll L, Woo SY, Donaldson S, et al. (1990) Nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the young: a combined MD Anderson and Stanford experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 19(4): 881-887. [Ref.]

- Ayan I, Altun M. (1996) Nasopharyngeal carcinoma in children: retrospective review of 50 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 35(3): 485-492. [PubMed.]

- Cvitkovic E, Bachouchi M, Armand J-P. (1991) Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Biology, natural history, and therapeutic implications. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 5(4): 821-838. [PubMed.]

- Chang ET, Adami H-O. (2006) The enigmatic epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomarkers. 15(10): 1765-1777. [PubMed.]

- Zen HG, Jame J-M, Chang AY, et al. (1991) Nasopharyngeal carcinoma with bone marrow metastasis. Am J Clin Oncol. 14(1): 66-70. [PubMed.]

- Sultan I, Casanova M, Ferrari A, Rihani R, Rodriguez‐Galindo C. (2010) Differential features of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in children and adults: a SEER study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 55(2): 279-284. [PubMed.]

- Andersson‐Anvret M, Forsby N, Klein G. (1977) Henle W. Relationship between the Epstein‐Barr virus and undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Correlated nucleic acid hybridization and histopathological examination. Int J cancer. 20(4): 486-494. [PubMed.]

- Bar‐Sela G, Ben MWA, Sabo E, Kuten A, Minkov I, et al. (2005) 45Pediatric nasopharyngeal carcinoma: better prognosis and increased c‐Kit expression as compared to adults. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (3): 291-297. [Ref.]

- Downing NL, Wolden S, Wong P, Petrik DW, Hara W, et al. (2009) Comparison of treatment results between adult and juvenile nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 75(4): 1064-1070. [PubMed.]

- Ayan I, Kaytan E, Ayan N. (2003) Childhood nasopharyngeal carcinoma: from biology to treatment. Lancet Oncol. 4(1): 13-21. [PubMed.]

- Liu W, Tang Y, Gao L, et al. (2014) Nasopharyngeal carcinoma in children and adolescents-a single institution experience of 158 patients. Radiat Oncol. 9(1): 1-7. [Ref.]

- Ozyar E, Selek U, Laskar S, et al. (2006) Treatment results of 165 pediatric patients with non-metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a Rare Cancer Network study. Radiother Oncol. 81(1): 39-46. [PubMed.]

- Kao W-C, Chen J-S, Yen C-J. (2016) Advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma in children. J Cancer Res Pract. 3(3): 84-88. [Ref.]

- Uzel Ö, Yörük SÖ, Şahinler İ, Turkan S, Okkan S. (2001) Nasopharyngeal carcinoma in childhood: long-term. results of 32 patients. Radiother Oncol. 58(2): 137-141. [PubMed.]

- Zubizarreta PA, D’Antonio G, Raslawski E, et al. (2000) Nasopharyngeal carcinoma in childhood and adolescence: a single‐institution experience with combined therapy. Cancer. 89(3): 690-695. [PubMed.]