>Corresponding Author : Khurram Shehzad

>Article Type : Case Report

>Volume : 3 | Issue : 2

>Received Date : 22 Feb, 2023

>Accepted Date : 02 March, 2023

>Published Date : 07 March, 2023

>DOI : https://doi.org/10.54289/JCRMH2300110

>Citation : Shehzad K, Anwar MS, Alrajhi N and Aldehaim M. (2023) Formation of Diagonal Gaps as Stress-Relieving Sites: Rethinking the Concept of Increment Splitting in Direct Occlusal Composite Restorat Carotid Sinus Syndrome in a Patient of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Treated with Palliative Radiotherapy. J Case Rep Med Hist 3(2): doi https://doi.org/10.54289/JCRMH2300110

>Copyright : © 2023 Shehzad K, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Case Report | Open Access

Department of radiation and medical oncology (Oncology center), King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research center, Riyadh, KSA

*Corresponding author: Khurram Shehzad, Department of radiation Oncology (Oncology center), King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research center, Riyadh, KSA.

Abstract

Carotid sinus syndrome leading to bradycardia, unconsciousness and eventually cardiac arrest is a rare condition. Its pathophysiology is not fully understood. Here, we present a rare case of a 79-year-old male with left cervical lymph node metastasis originating from primary carcinoma of nasopharynx. He was admitted to hospital with history of recurrent syncopal episodes at home. Paroxysms of extreme bradycardia (Heart rate of < 40) were detected during hospital stay. CT-scan and MRI of neck revealed compression of left neck vasculature. This patient was treated with palliative radiotherapy. He showed favorable response in that he became asymptomatic.

Abbreviations: CSS: Carotid Sinus Syndrome, LOC: Loss of Consciousness, CPR: Cardio Pulmonary Resuscitation, ROSC: Return of Spontaneous Circulation, EEG: Electroencephalogram, ICU: Intensive Care Unit, ICA: Internal Carotid Artery, IJV: Internal Jugular Vein, CTV: Clinical Targe Volume, PTV: Planning Target Volume, IVC: Inferior Vena Cava

Introduction

Carotid sinus hypersensitivity has been known for a long time. In patients with head and neck cancer, syncope may appear as an initial manifestation of the disease, as a side effect of surgery or radiotherapy or as an indicator of local recurrence [1].

Three syndromes with distinct pathophysiology have been described in literature. One is carotid sinus syndrome (CSS) due to compression or invasion of the carotid sinus. It triggers an overactive reflex and strong efferent vagal response that may result in sinus bradycardia, sinus arrest or atrioventricular conduction disturbances. Other two are “glossopharyngeal-asystole neuralgia syndrome”, due to spontaneous afferent impulses of the glossopharyngeal nerve; and “para-pharyngeal space syndrome” due to compression or invasion of the para-pharyngeal space and stimulation of glossopharyngeal afferent fibers by tumor. In addition, another condition also described in literature sometimes is “baroreceptor reflex failure syndrome”. This usually occurs secondary to surgery or radiotherapy. These disorders cause reflex mediated modification in vascular tone or heart rate, characterized by failure of autonomic nervous system to maintain cerebral perfusion leading to sudden loss of consciousness [2]. Head and neck tumors are rare to cause carotid sinus hypersensitivity. However, when it happens, most cases occur in the presence of extensive cervical lymph node involvement [3,4].

There is no universally effective treatment for patients with syncope caused by head and neck malignancies. Previously investigated treatments include vasoconstrictive drugs, cardiac pace makers, radiotherapy and surgical removal of glossopharyngeal nerve. For Head and neck tumors causing carotid sinus syndrome, radiotherapy can be effective [3]. Definitive treatments consist of surgical removal of the tumor or radiotherapy especially if tumor is considered surgically un-resectable as in our case [5].

Case Presentation

A 79-year-old male presented to our oncology center in January 2021 with complaints of nasal obstruction, headache, bilateral neck masses and decreased hearing. He had outside CT and MRI that showed enlarged bilateral neck nodes, larger on left side. Scans also showed left sided nasopharyngeal mass. Clinically he had bilateral neck adenopathy, bulky on left mainly at levels 2, 3 and 4.

His nasopharyngeal mass evident on nasoendoscope was biopsied. Biopsy confirmed it to be carcinoma of Nasopharynx (non-keratinizing) undifferentiated type. Base line staging workup including CT Head and Neck, CT chest abdomen and Pelvis, MRI Neck and Brain and whole body PET-CT scan confirmed it to be a T3 primary tumor of nasopharynx with bulky bilateral nodes N3 (left supraclavicular adenopathy). There were radiologically evident distant metastases. PET-CT showed FDG avid liver lesions and multiple abdominal lymph-adenopathy including porta-hepatis, gastro-hepatic, retro-caval and right retro crural region. Multiple FDG-avid sub carinal/ right para esophageal lymph nodes were also found.

There were very high levels of detectable EBV in his blood measuring 7978 IU/ml.

He started on systemic chemotherapy in the form of Cisplatin and Docetaxel in February 2021. He tolerated it poorly with neutropenic sepsis. Subsequent therapy changed to oral Capecitabine at 850mg/m2 BID for 14 days of a three weekly cycle, in March 2021. After 4 cycles of Capecitabine, restaging PET scan in May 2021 showed near complete resolution of nasopharyngeal mass, neck adenopathy and liver lesions. He continued same therapy for total of 6 months. His follow up PET-CT in September 2021 showed interval progression in neck nodes and liver lesions whilst still on oral Capecitabine. Once again, he had platinum and taxanes containing regimen with dose reduction. Repeat restaging PET scan imaging after 4 cycles of chemotherapy showed stable disease in neck and liver. He was advised follow up with no further chemotherapy after completing 6 cycles of same regimen.

Patient presented again with progression in neck nodes and liver lesions in Feb 2022. This time he received yet more chemotherapy in the form of single agent Gemcitabine. Follow up imaging showed responding disease in neck and liver. Same chemotherapy was continued until June 2022. Further chemotherapy was stopped due to poor tolerance.

He presented to Emergency room in August 22 with history of seizures in form of transient loss of consciousness (LOC) lasting a few minutes each. He was admitted for further evaluation. Within 24 hours of hospital admission, he had loss of consciousness along with cardiac arrest that needed Cardio Pulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) for return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC). The patient was shifted to intensive care unit (ICU) and Cardiology and neurology teams were involved while he was in ICU. The CT brain done in emergency was negative for any acute abnormality.

Surprisingly “twenty-four hour holter monitoring” failed to show any episode of significant bradycardia. Similarly, bedside echocardiography was unremarkable apart from collapsible inferior vena cava (IVC). The impression of cardiology team was that the multiple episodes of LOC were most likely vasovagal in etiology and could be related to tumor compressing carotid sinus causing carotid sinus hypersensitivity (CSH). He had bradycardia of 30-40 beats per minute during the episodes but no pause of > 3 seconds to meet criteria for cardio inhibitory (bradycardia) response. It was likely that vasodepressor response (hypotension) was dominant. He was intubated for loss of consciousness (LOC) and bradycardia. However, he was extubated next day as there were no other significant concerns about his heart or lungs. During his ICU stay, he had multiple episodes of loss of consciousness with labored breathing, along with bradycardia and hypotension. Electroencephalogram (EEG) done three times, yet all three were negative for brain seizure activity. The episodes aborted with lorazepam and atropine. The neurology team concluded that nothing more needed from their side.

Patient had cardiac arrest many times during his ICU stay, achieving ROSC after CPR and did not require intubation again.

As per consensus of Radiation and medical oncology teams, PET-CT and MRI brain were requested while in ICU to restage his disease.

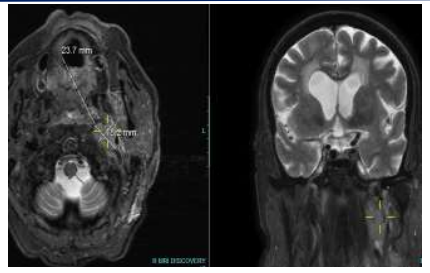

His repeat imaging including MRI showed multiple metastatic cervical lymph nodes, the largest in the left carotid space encasing the left internal carotid artery (ICA) and compressing the left internal jugular vein (IJV).

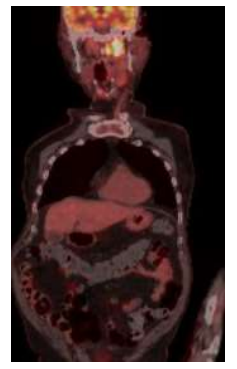

PET-CT scan revealed interval progression of the scattered bilateral FDG-avid cervical lymph nodes. There were also FDG-avid hepatic lesions worrisome for metastasis and small bilateral pleural effusion showing mild FDG activity.

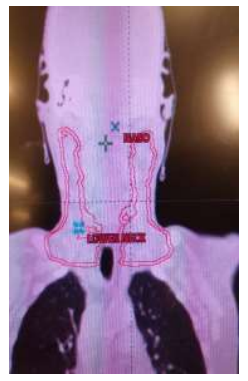

Considering his repeated episodes of transient unconsciousness, cardiac arrest and recovery with CPR, along with imaging showing significant compression of left sided ICA and IJV, he was offered radiotherapy to neck nodal disease. Radiotherapy started on of 24/8/2022 with 3D conformal radiation plan aiming to deliver 20Gy in five fractions.

The radiotherapy volumes covered Nasopharyngeal primary tumor area and bilateral neck nodal region including Level2, level 3, 4 and 5 going down to supraclavicular area bilaterally.

After start of radiation, he only had one episode of bradycardia from which he recovered spontaneously without any medication. There were no more episodes of loss of consciousness or cardiac arrest. The patient moved out of ICU after 2 fractions of radiotherapy as his condition remained stable in ICU. He completed rest of three radiation fractions in regular inpatient unit without any further syncope, bradycardia or cardiac arrest. After staying under observation for a couple of days more he went home in stable condition.

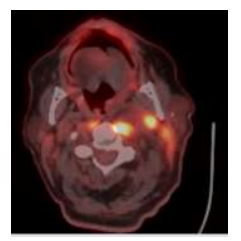

His pre radiotherapy PET-CT (axial image) showing left sided FDG avid adenopathy.

Coronal PET image of the pre radiotherapy PET-CT.

MRI images showing left sided neck nodes compressing carotids (axial and coronal images).

Radiotherapy plan images

This an axial CT image of radiation planning CT, showing Clinical Target Volume ( CTV, inner contour line) and Planning Target Volume (PTV, outer contour line) with 3mm margins to CTV at level of neck.

This is a coronal CT image of radiation planning CT showing CTV ( inner line of contour) and PTV with 3mm margins to CTV. The proximal and distal margins for the CTV and PTV can be viewed.

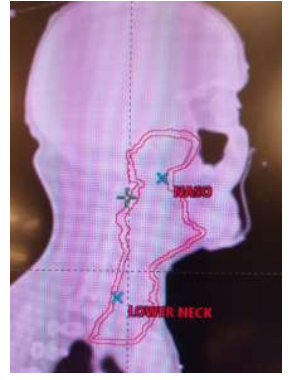

The sagital image of the same planning CT along CTV and PTV with 3mm margins to CTV, again showing proximal volume covering up to base of the skull and distally going down to supraclavicular area.

Discussion

We discuss a case of metastatic carcinoma of nasopharynx who progressed on multiple lines of chemotherapy and then presented in ER with syncopal attacks and bradycardia.

Cardiac and neurological investigations did not reveal an obvious cause for these symptoms. However, radiological evaluation showed compression of left carotid vasculature. Involvement of carotid sinus was thought to be the most likely cause of these symptoms. Multiple episodes of loss of consciousness, bradycardia and cardiac arrest, were managed with medications. They only provided temporary relief. Palliative course of radiotherapy to the affected area was the modality, which made patient’s symptoms, go away permanently.

Toscano, M and colleagues have recently reported a case of H&N cancer with occult primary and similar successful outcome with radiotherapy [5]. However, in our knowledge, metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma causing CSS is extremely rare and there are only a handful cases with either proven nasopharyngeal primary or suspected primary nasopharyngeal carcinoma have ever been reported.

Of course, there is no universally accepted effective treatment for such patients. Different treatment modalities investigated previously include vasoconstrictive drugs, cardiac pacemakers etc. generally and radiotherapy and/or surgical resection of the glossopharyngeal nerve more specifically [6].

A literature review using Med line has been published. It included 12 papers with 41 patients reporting CSS symptoms associated with head and neck cancers. The average time to develop syncopal symptoms was 10 months. Fifteen patients developed syncope post treatment as a symptom of recurrent disease [6].

In carotid sinus syndrome, radiotherapy seems effective for head and neck malignancy [3]. There is limited, if any, benefit of electrophysiological intervention. Pharmacological therapy is found to be effective in some but not all patients. Surgical and radio therapeutic treatment of underlying disease have been most effective in controlling symptoms of syncope [6].

Hence, we suggest that when patients with head and neck cancer present with syncopal symptoms, one should have high index of suspicion for this condition. We should investigate such patients keeping in mind the possibility of tumor mass being close to or involving Carotid sinus as the cause. Management should take into account all factors including fitness, prognosis of individual patient and treatment options available. Amongst non-surgical options, local radiotherapy may be given serious consideration as a quick and effective intervention.

References

- Newton HB & Malkin MG. (2010) Neurological Complications of Systemic Cancer and Antineoplastic Therapy. CRC Press. 1st ed. [Ref.]

- Kapoor WN. (2000) Syncope N. Engl J Med. 343: 1856-1862. [PubMed.]

- Macdonald DR, Strong E, Nielsen S, Posner JB. (1983) Syncope from head and neck cancer. J Neurooncol. 1(3): 257-267. [PubMed.]

- Papay FA, Roberts JK, Wegryn TL, Gordon T, Levine HL. (1989) Evaluation of syncope from head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 99(4): 382-388. [PubMed.]

- Toscano M, Cristina S, Alves AR. (2020) Carotid Sinus Syndrome in a Patient with Head and Neck Cancer: A Case Report. Cureus. 12(2): e7042. [PubMed.]

- Bauer CA, Redleaf MI, Gartlan MG, Tsue TT, McColloch TM. (1994) Carotid sinus syncope in head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 104(4): 497-503. [PubMed.]