>Corresponding Author : Muntadher Abdulkareem Abdullah

>Article Type : Case Report

>Volume : 3 | Issue : 4

>Received Date : 07 April, 2023

>Accepted Date : 17 April, 2023

>Published Date : 21 April, 2023

>DOI : https://doi.org/10.54289/JCRMH2300116

>Citation : Abdullah MA. (2023) Autoimmune Hepatitis Induced by Acute Hepatitis A Infection (Unusual Complication). J Case Rep Med Hist 3(4): doi https://doi.org/10.54289/JCRMH2300116

>Copyright : © 2023 Abdullah MA. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Case Report | Open Access

Lecturer at Basrah college of Medicine, Basrah Gastroenterology and Hepatology Hospital

*Corresponding author: Muntadher Abdulkareem Abdullah, Lecturer at Basrah college of Medicine, Basrah Gastroenterology and Hepatology Hospital

Key words: Autoimmune Hepatitis; Hepatitis A Infection; Anti-Smooth Muscle Antibody

Abbreviations: HAV: Hepatitis A Virus, AIH: Autoimmune Hepatitis, CBC: Complete Blood Count, ASMA: Antismooth Muscle Ab

Introduction

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) is an enteric-transmitting virus and the most common cause of acute viral hepatitis worldwide [1]. Generally, in childhood, the infection is asymptomatic or anicteric; however, it is often more severe in adults. Acute hepatitis A infection can be diagnosed by the detection of the immunoglobulin M antibody against HAV (AntiHAV IgM) in patients who have the clinical features of hepatitis, on the other side the autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic liver disease characterized by circulating autoantibodies, elevated immunoglobulin G levels and characteristic histologic changes and when untreated can lead to acute liver failure or chronic liver disease resulting in cirrhosis. While the etiology of AIH is not entirely known, an association with human leukocyte antigen types DR3 and DR4 has been described [2]. Various viral triggers for AIH have been described, including the Epstein Barr virus, herpes simplex virus, HIV, and hepatitis A, B, C, and D viruses, specifically in genetically susceptible individuals [3]. Rare instances of AIH following acute hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection have been reported.

The diagnosis of AIH in the setting of HAV and the decision to start immunosuppressant therapy continues to be a management dilemma for hepatologists. To address this dilemma, there have been reports of prolonged acute HAV infection that can mimic AIH [4].

In this case report, I present the case of a 42-year-old male patient who was diagnosed with AIH six months after acute hepatitis A infection.

Case presentation

42-year-old male patient, immunocompetent with no previous history of liver disease, no history of alcohol consumption, no history of hepatotoxic drug or herbal ingestion, presented with three days history of sever jaundice, abdominal pain, fever, dark colour urine associated with nausea, anorexia and repeated vomiting.

On examination, the patient was conscious, oriented, looked ill, had deep jaundice, vitally stable, febrile(temperature = 38.8 C), tender hepatomegaly (liver palpable 2 cm below the right costal cartilage mid-clavicular line), no splenomegaly, and no lymphadenopathy.

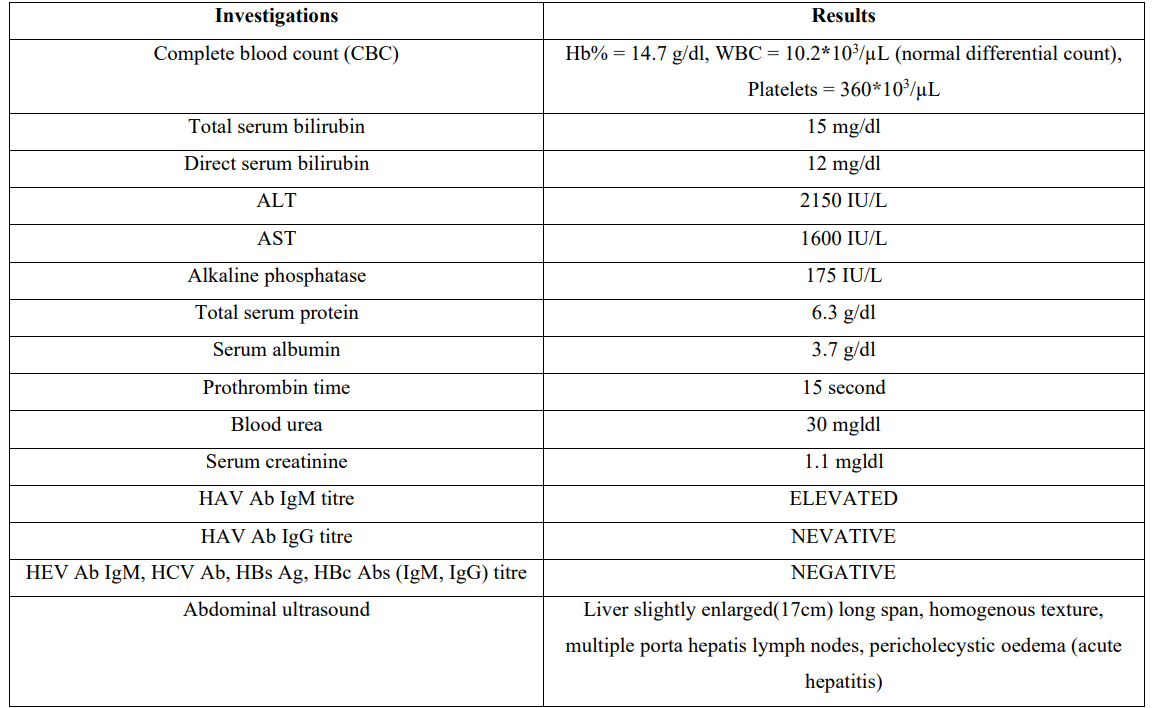

Investigation was done for him and revealed the following:

Table 1

Based on the history, physical examination and the investigations, the patient was diagnosed with acute hepatitis A infection, the patient admitted to the hospital for supportive treatment and monitoring, after seven days of hospital admission the patient condition greatly improved with resolution of jaundice, fever, abdominal pain and improvement of the appetite and resolution of the vomiting, so the patient discharged home, the liver enzymes and the total serum bilirubin return to normal reference levels on the second week outpatient follow up.

Six months after the diagnosis of acute hepatitis A infection, the patient returned to the hepatology outpatient clinic in our hospital when he noticed that his sclera turned yellow with deepening of the urine color associated with fatigue and decreased appetite.

On examination, the patient was fully conscious and oriented, jaundiced, vitally stable, afebrile, and had no organomegaly or lymphadenopathy.

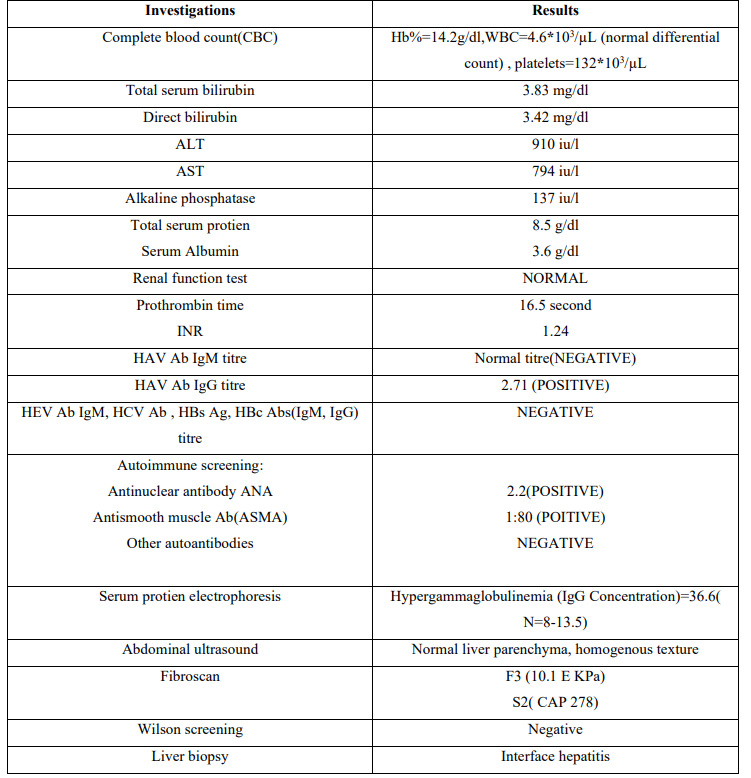

Investigations revealed the following:

Table 2

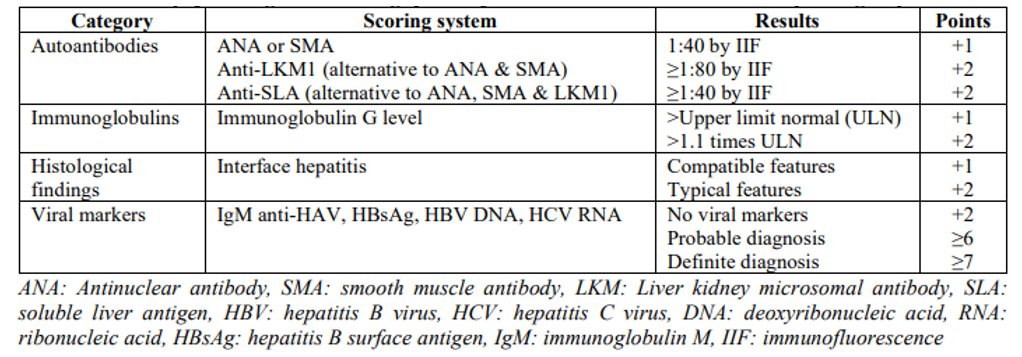

Therefore, a diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis(AIH ) was established using the simplified criteria given by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (Table 3). The patient’s score was 7, which was suggestive of a definitive diagnosis of AIH.

Table 3. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group

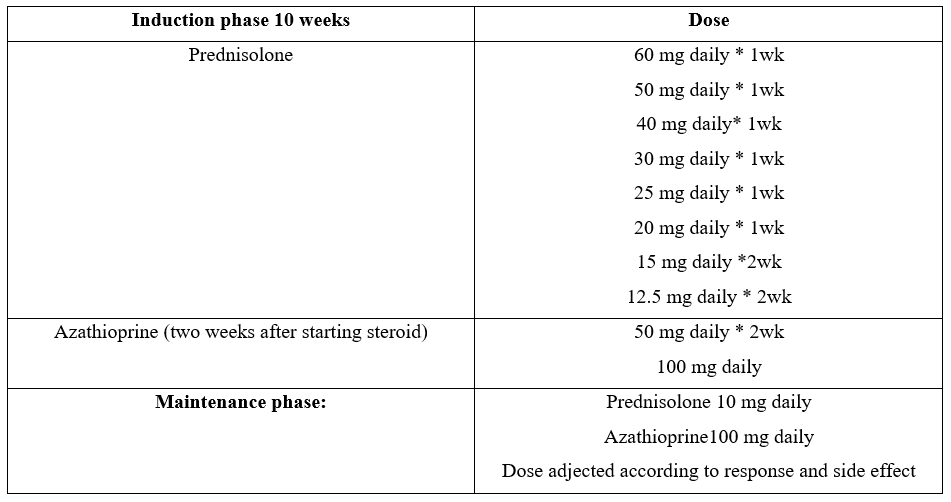

He was treated with oral prednisolone 60 mg/day for 2 weeks, after that Azathioprine was added at a dose of 50 mg/day, then the steroid dose tapered gradually and azathioprine dose increase to 100 mg/day, in a manner according to (British society of Gastroenterology BSG/European Association for study of liver disease EASL) shown in table(4).

Table 4. BSG/EASL - endorsed combination regimens

The patient showed an excellent response to treatment without significant side effects. His liver function tests were regularly monitored during the treatment, and there was improvement in the liver enzyme level, serum bilirubin, coagulation profile, normalization of liver function tests, and serum bilirubin, hypergammaglobulinemia, and fibroscan score at the end of the tenth week of starting treatment. The patient was now on maintenance treatment and his condition was controlled.

Discussion

Hepatitis viruses A, B, and C can play a role in the development of AIH in adults [5]. Liver damage after acute viral hepatitis A is associated with HLA DR13, a genetic marker of AIH [6]. T regulatory cells regulate the immune response by their immunoregulatory action, preventing proliferation and subduing the function of autoreactive T cells. This response is hampered by AIH [7].

Vento ST, et al [8] studied 58 first- and second-degree relatives of 13 patients of acute hepatitis A to determine whether AIH occurs in patients who are genetically predilected to a defect in asialoglycoprotein receptor defect, triggered by an unknown factor like a virus or a drug. They concluded that the autoimmune response mediated by these antibodies manifests because viral hepatitis A infection causes a defect in suppressor inducer T cells. Thus, there is a complicated relationship between acute viral hepatitis A and AIH development. Whether hepatitis A infection triggers the development of AIH or exacerbates an existing asymptomatic AIH remains a matter of debate.

AIH may be asymptomatic in 25–34% of patients or present with fulminant hepatitis [9]. The characteristic biochemical parameters of AIH are the presence of serum autoantibodies, antinuclear antibodies, and anti-smooth muscle antibodies in type I AIH and anti-liver kidney microsomal I/III antibodies and anti-liver cytosol antibodies in type II AIH, hypogammaglobinemia, and elevated levels of immunoglobulin G [9]. The titers of these autoantibodies not only help in making the diagnosis but also in monitoring the disease course. Liver histology also plays a major role in the diagnostic workup, where piecemeal necrosis, hepatocyte rosetting, and periportal inflammation are some clues for diagnosis [10].

Conclusion

Hepatitis A viral infection can trigger the development of AIH or exacerbate the existing asymptomatic AIH. Therefore, patients with acute viral hepatitis A infection should be regularly followed up, and if they present with another similar episode, AIH should be kept in mind, as the early initiation of treatment can significantly reduce morbidity and mortality.

References

- Tosun S, Ertan P, Kasirga E, Atman U. (2004) Changes in seroprevalence of hepatitis A in children and adolescents in Manisa, Turkey. Pediatr Int. 46: 669-672. [PubMed.]

- Hilzenrat N, Zilberman D, Klein T, Zur B, Sikuler E. (1999) Autoimmune hepatitis in a genetically susceptible patient: is it triggered by acute viral hepatitis A? Dig Dis Sci. 44(10): 1950-1952. [PubMed.]

- Manns MP. (1997) Hepatotropic viruses and autoimmunity 1997. J Viral Hepat. 4(Suppl 1): 7-10. [PubMed.]

- Mikata R, Yokosuka O, Imazeki F, Fukai K, Kanda T, et al. (2005) Prolonged acute hepatitis A-mimicking autoimmune hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 11(24): 3791-3793. [Ref.]

- Christen U, Hintermann E. (2019) Pathogens and autoimmune hepatitis. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 195(1): 35-51. [Ref.]

- Tabak F, Özdemir F, Tabak O, Erer B, Tahan V, et al. (2008) Autoimmune hepatitis induced by prolonged hepatitis A virus infection. Annals of Hepatology. 7(2): 177-179. [PubMed.]

- Longhi MS, Ma Y, Bogdanos DP, Cheeseman P, Mieli-Vergani G, et al. (2004) Impairment of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T-cells in autoimmune liver disease. Journal of Hepatology. 41(1): 31-37. [PubMed.]

- Vento ST, Garofano T, Dolci L, Di Perri G, Concia E, et al. (1991) Identification of hepatitis A virus as a trigger for autoimmune chronic hepatitis type 1 in susceptible individuals. Lancet. 337(8751): 1183-1187. [PubMed.]

- Czaja AJ. (2016) Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis: Current status and future directions. Gut and Liver. 10(2): 177-203. [Ref.]

- Tiniakos DG, Brain JG, Bury YA. (2015) Role of histopathology in autoimmune hepatitis. Digestive Diseases 33(Suppl 2): 53-64. [PubMed.]