>Corresponding Author : Halldór Bjarki Einarsson

>Article Type : Short Report

>Volume : 1 | Issue : 1

>Received Date : 03 Jan, 2023

>Accepted Date : 13 Jan, 2023

>Published Date : 19 Jan, 2023

>DOI : https://doi.org/10.54289/JPBT2300101

>Citation : Lützhøft JH and Einarsson HB. (2023) Case report: Saving a life by poem. J Psychol Behav Ther 1(1): 1-6. doi https://doi.org/10.54289/JPBT2300101

>Copyright : © 2023 Lützhøft JH, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Short Report | Open Access

1Department of Psychiatry, Aarhus University Hospital‚ Denmark

2Department of Neurosurgery, Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark

*Corresponding author: Halldór Bjarki Einarsson, Department of Neurosurgery, Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark

Abstract

The present Old Norse case report concerns how a poem saved the life of the famous viking, named Egil Skallagrimsson. By some scholars he has been considered a person with dissocial personality disorder, i.e., psychopathy correlates - although not completely - to antisocial personality disorder, a personality disorder in the cluster B type. A core symptom of dissocial personality disorder is lack of empathy. The craving for appreciation and fulfilment of own needs is moreover a part of the disorder. Furthermore, an incredibly good ability to explain away actions and to project outwards, a low threshold of aggression, and the lack of responsibility are found. All together an alloplastic personality disorder with a tendency to blame the surroundings for the problems [1-3]. For the general population, exact epidemiological data on psychopathy prevalence does not exist. However it is estimated to be 3% in forensic psychiatric samples [4]. For adult male offenders, structural abnormalities in the cingulate have recently been reported to correlate with the gold standard diagnostic criteria (Psychopathy Checklist-Revised) for psychopathy [5]. The eminent power to manipulate others is not rare in these individuals [3]. Can a psychopath, however, captivate another psychopath? Reading the Old Norse Kings Saga, Heimskringla, you may wonder whether this could be a possibility, as described in the oral tradition 1000 years ago, later written down by most likely Snorri Sturluson, considering the meeting between Egil Skallagrimsson and Eric Bloodaxe. Once investigating this stunning Icelandic saga characters, it often falsely leads to the conclusion of a psychopath diagnosis or their suffering from other personality disorders rather than just enjoying the storytelling.

Keywords: Narrative medicine; Egil’s Saga; Personality disorders; Poem

Introduction

Both throughout history and among the powers that be today can be noticed a behaviour in some of the rulers and their surroundings, concerning their actions and their need of appreciation, which, seen from the outside, leaves the impression of psychopathic traits. The actions of a person in power can, however, also be regarded as dictated by "the impotence of power". That is, a ruler in a game of power has had limited options and has almost been forced to follow a manuscript. In viewing actions of the past, the reader may additionally have to consider that what presently would be evaluated as severely deviant behavior, may have been considered something you would expect, in the context of for instance year 900-1000. Furthermore, through history aspects may have been lost in the retelling, writing, rewriting, and translating. Elements may also have been added during the retelling, rewriting, and translation. Variations of the saga exist. The meeting in York between Egil, as presented in the following, and the exiled Norwegian royal couple, King Eric Bloodaxe and Queen Gunhild, is one of the episodes leaving such an impression.

Egil Skallagrimsson cannot be regarded as the dream of all mother-in-laws, neither now nor then. He was viewed as being “no beauty” and his inner self seemed to reflect his exterior looks. He committed his first killing at 8 or 9 years old, when he slashed an axe into the head of a few years older playmate from behind. When grown-up he spread havoc and killed. What might have been the child’s prodigy’s double-edged sword in the view of his times? He could read, write, and wrote poetry. In York, Egil was set before King Eric, who had a whole series of reasons to order him to be killed. Yet after Egil had recited a poem, he was allowed to go. Why? The relation of the families of Eric Bloodaxe and Egil Skallagrimsson were complicated. The father of Eric Bloodaxe, Harald Fairhair, had ordered the brother of Egil's father to be killed and had participated actively in the killing. Taking revenge, Egil's father, Skallagrim, and his father attacked one of Harald Fairhair's ships and killed almost everyone on board, including two of Harald Fairhair's relatives. Afterwards they left Norway and sailed to Iceland. Thus, Harald Fairhair felt he had an unfished score with the family of Skallagrim.

Methods

A retrospective analysis with text mining and bibliometric

Case Description

When Eric was not yet a king, but only one of several sons of a king, Egil's brother, Thorolf, gave him a ship for 30 men, a karve. In gratitude, Eric promised Thorolf friendship, claiming this could be deemed but a poor payment - "but this thou mayest look for if I live" [6]. If you were one of several sons of a king, life could be somewhat insecure. Then Eric interceded for Thorolf with his father the king. This did not please Harald Fairhair. Later when Eric was endowed with the areas Hardaland and the Fjords, Thorolf fought for him. Thorolf was also befriended by the wife of Eric Bloodaxe, Gunhild – until Egil came, along. When the royal couple met in York, they also had their personal reasons to feel anger toward Egil. This can be considered to be partly mutual.

Being frustrated firstly by having been given junket (a dish of sweetened and flavoured curds of milk) instead of beer, which had been hidden for the expected arrival of the royal couple and their entourage, when Eric was finally given beer, he sang bitter verses. Following this, after consulting Gunhild, the host Baard served poisoned beer to Egil and his mates. In the tumult that followed, Egil killed Baard. From Egil's point of view this is understandable, following from first being given junket instead of beer, then beer brought clandestinely, and finally given poisoned beer. Fleeing from the scene, Egil killed three of the king's men and stole a boat. The problem of the three dead men was solved by a fine for manslaughter, under the condition that Egil leave Norway.

When the possibility came up of allowing Egil to stay in Norway anyway in spite of his actions, Gunhild was outraged. She claimed Eric Bloodaxe would spare these sons of Skallagrim until they once more would be the death of some of his nearest kinsmen. Her anger also turned against Egil's brother. She said Thorolf was well esteemed until Egil came and claimed that she now saw them as one.

Gunhild did not stop there. Before a great blót (Nordic ritual including sacrifice) in which Egil was expected to participate, she spoke with two of her brothers, saying that among so many people you might easily happen to kill somebody. She told them she preferred that it would be one of the sons of Skallagrim, at best both. A friend of Egil made sure that he was not present at the blót. In frustration, one of the brothers, Ejvind Skreja, killed a man in Thorolf's entourage. Since the killing took place in a sacred place, and Thorolf and his friend rejected the offer of a fine for manslaughter, Queen Gunhilds brother, Ejvind Skreja, had to leave Norway as an outlaw. Later Egil Skallagrimsson attacked and took two ships of Ejvind Skreja opposite the coast of Jutland, killing a great number of the men on board, but some escaped by swimming away, including Ejvind Skreja.

Later yet, under a negotiation at "tinget" (a mixture of court and parliament) in Norway, it was discussed whether or not the wife of Egil was entitled to inherit from her family.

Gunhild raised her voice against Egil's claim. Egil challenged the king to a single combat. Fleeing from the place, with a well-thrown spear Egil killed the king's entrusted man who was steering the king's ship. This man stood where the king would be expected to stand. Having done this, Egil made a poem of malice. In this he invoked all powers and gods to dispel Eric out of the country. Egil also made another poem describing the king negatively. Leaving Norway, Egil heard the king had made him an outlaw. He then seized a ship with one of the sons of the royal couple, a promising boy 10 or 11 years old. The boy and his entourage, all in all 13 persons, were killed.

Discussion

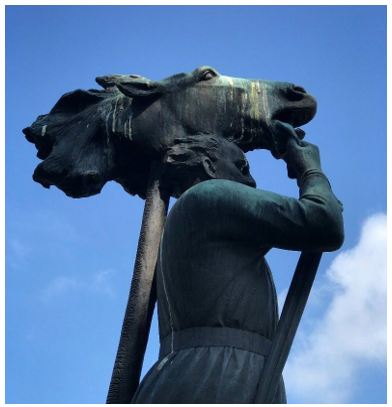

Before Egil finally left Norway, he put a horse-head on a nithing (curse-pole), on which he had carved runes with curses, so that the “land wights” (i.e. the spirits of the land in Norse Mythology and Germanic Neopaganism) would not get any rest before they had driven King Eric and Gunhild out of the country (figure).

Figure: “Egil Skallagrimsson raises a nithing pole” by sculptor Gustav Vigeland in Mandal (with courtesy of Vigeland Museum and Sculpture Park, Oslo, Norway). The same sculptor was the designer of The Nobel Peace Prize Medal. Hence the above interpretation of the sculptor can be said to represent everything opposite to friendship and harmony in the absence of hostility and violence.

The poems and the carving of runes in those days were regarded as more than impoliteness, being viewed as magical tools to bring about the intension in the writing's content. Shortly afterwards, Eric Bloodaxe and Queen Gunhild were driven out of Norway by Hakon Athelstenfostre, another son of Harald Hairfair. Thus, Egil had, from the viewpoint of the royal couple, offended them on a series of counts of which most were so severe that they should lead to capital punishment. King Eric – and the queen – must also have had an utterly bitter feeling at the news of the killing of their son, seen in the light of the warnings given to Eric by his own father and wife. Further stressing the internal relations of the couple would be the earlier discussion of how to react to the killing of Baard.

Eric Bloodaxe was not the type who was sitting and weeping during hardship. The couple went with their followers, including Egil's friend Arinbjorn, to England. Eric Bloodaxe was made leader of the territorial force of Northumberland. The exiled court took York as their residence. Queen Gunhild, who earlier in the saga was described as the most beautiful of all women, the wisest, and furthermore skilled with supernatural substances, boiled a pot of sejd (a magic mixture) saying words which would cause Egil to not find rest until he had met her and King Eric again.

Egil grew melancholy in Iceland [7] and went on a voyage.

Under a storm, he was shipwrecked on a coast in Eric's territory. Instead of the humiliation of being caught fleeing, which would have been likely if he had tried to flee, after consulting Arinbjorn, Egil chose to face the king. During the night Arinbjorn, who was liked by the king, spoke for Egil. The queen wanted Egil taken out and beheaded instantly. Arinbjorn claimed it was inappropriate to behead people at night. This was accepted as they may have been afraid of trolls (giants, demons, daugar/ghosts). Bearing in mind the complexity of human behaviour and experience, a troll-like paranormal experience is not only an Old Norse idea (where trolls visit humans during the night or in a dream) but can be viewed as the cause of hypnagogic hallucination, considering modern day psychiatric terminology [8,9].

Egil was informed that he would face the royal couple at daytime. He could use the night to compose a poem of praise dedicated to the king. Eric's composing was distracted by a swallow sitting in the peephole (and perhaps queen Gunhild had an amount of sejd corresponding to a cup of instant tea left). Arinbjorn joined Egil, sat by the peephole and drove the swallow away (magic frail swallows are apparently frightened by broad-shouldered vikings). Egil composed to save his life. The next day Egil faced the royal couple. Not surprisingly the queen still advocated a short process.

At the meeting the night before, Arinbjorn had portrayed Egil's arrival to the court as if Egil himself had chosen to meet the king, making the long voyage from his home to York, in order to receive his pardon - a somewhat poetic description of the consequence of a shipwreck. He made the point that Egil through a poem of praise could neutralize the calamity of the runes of the nithing/curse-pole bearing the horse-head (figure). Arinbjorn moreover drew attention to the fact that Eric Bloodaxe's father had ordered the killing of Egils's father's brother and participated in this, due to no other reason as an act of evil. By letting Eric go, the king could correct an injustice on the behalf of his family.

In the second defense by Arinbjorn, he came with all his men, of whom half were allowed to enter. Arinbjorn stated that Egil had not tried to escape during the night. Arinbjorn himself had served Eric Bloodaxe, done much for him and by following Eric to England lost his property in Norway. Egil should at least be given a week to escape. There would not be much prestige in killing a foreign yeoman's son who had come to throw himself onto the mercy of the king. Then Arinbjorn threw his master card: "but if the king wishes to achieve greatness hereby, then I will help him in this, so that these tidings shall be thought more worthy of record: for Egil and I will now back each other, so that we must be met at once. Thou wilt then o king dearly buy the life of Egil, when we all laid dead on the field, I and my followers. Far other treatment should I have expected of thee, than that thou wouldst prefer seeing me laid dead on the earth to granting me the boon I crave of one man's life" [6].

Egil now recited the poem of praise. King Eric Bloodaxe then made a decision which is likely to have led to "back to back" in the royal bed for some time: "Right well was the poem recited" [6]. The king then acclaimed his respect for Arinbjorn, and he furthermore described the possible killing of Egil in the given situation as a "dastardly deed" [6], indicating that he agreed with Arinbjorn on this item and then came the quite weak rider: “but next time”. Egil became so grateful that he recited a bonus poem with the point that his head was ugly, so it was a poor gift, but letting it be in its place was the greatest gift to him.

Regarding the defense made by Arinbjorn, you could claim that he appealed to the king's feelings of honor and justice, and on behalf of the king's family, by proposing a barter deal exchanging Egil's life with the death of Egil's father's brother. Furthermore, Arinbjorn hinted that a poem of praise would counteract the devastating runes on the curse-pole and that the king was therefore more likely to consider how he could return to Norway. He additionally appealed to the king's feelings, which made it clear that Eric Bloodaxe could get both Egil and Arinbjorn killed, but at the cost of so many of his own men, that the king's army would be weakened. In a slightly more speculative point of view, further reasons for Erik's decision exist.

Concerning the king himself during the conflicts, Eric Bloodaxe often tried to soften the anger of his wife towards Egil. He agreed to accept blood money for his three dead men. Even though his byname, Bloodaxe, is unlikely to have been given to him because he slaughtered sheep at Sundays and gave their meat to the poor, Eric may have had an element of peacefulness within him. In addition, the relation between the spouses has to be considered. It may have been dysfunctional to some degree. Gunhild and Eric might not have been chosen as the most harmonic royal couple of the year. Perhaps the king wanted to signal to his wife, that it was not she who ruled. Queen Gunhild had been active in the struggle with Egil. She had done her part by Egil being given poisoned beer and had made the king and others infuriated with Egil and his family. Egil described this in one of his former poems against the king. He described the king as the law-breaker, the bloodaxe, fratricide, the felon, and then claimed in the poem that it was Gunhild the cruel who caused the persecution.

Perhaps Eric Bloodaxe may moreover have had some veneration or other feeling towards Egil's late brother, Thorolf. The picture seems unclear. During one of Gunhild's verbal attacks on the sons of Skallagrim, Eric indicated that once upon a time it had been “hot” between her and Thorolf. What did Eric mean by this? If you were told during the viking era about the meeting in York, or later read the saga in the times it was written, you may have considered Queen Gunhild boiling sejd and thus causing Egil to come, as a fact. And you may have speculated whether the magic of Gunhild worked, but apparently it was just the wrong man that was hit (i.e. Eric, who lost his judgment).

King Adalsten, of whom Eric can be said to be his vassal, was very fond of Egil. King Adalsten had moreover been very fond of Egil's dead brother, Thorolf, who fell in a battle fighting for Adalsten. Had King Adalsten and Eric Bloodaxe met and Adalsten asked for news about his good friend Egil, and Eric answered, oh by the way, I had him beheaded, it may not have been the best approach from an employee.

Furthermore, considering the very structure of the poem of praise:

Red blade the king did wield

Ravens flocked o'er the field

Dripping spears flew madly

Darts with aim flew deadly

Scotland's scourge let feed

Wolf the ogress' steed

For er'ne of downtrod dead

Dainty meal was spread

(Translation by W.C. Green) [6]

The poem rhymes and may be fitted for singing while rowing a ship, a hard monotonous work. It may also have been used, when standing before a battle in a wall of shields, hammering sword against shields. Nevertheless, and must likely, it would have taken some of the magic and force of the poem, if the men had known that on the pole to the right of the entrance to the royal estate was the head of the composer. The bonus poem seems more refined, but not fit for rowing or fighting. Finally, there is a consideration that the exiled King Eric Bloodaxe may have had. In our days it may seem remote, but considering his family story, he may have thought this. Eric had killed some of his own brothers and was driven out of Norway by a brother. By killing one of Eric's sons, Egil Skallagrimsson had assured that the one of Eric's sons who succeeded Eric after a possible regain of power in Norway, or who himself won Norway, would have a brother less to consider.

All in all, Eric had many good reasons for his decision. Did he have any real choice? If you wish to compare the two speeches of Arinbjorn with any other juridical speeches in history, you may with a bit of Schwung (swing) do this with the three speeches of defense by Socrates in the year 399 B.C. as described by Plato. Most will properly regard the speeches of Socrates as the greater input to history. On the other hand, the result of his speeches was that Socrates was sentenced by angry co-citizens to drink a cup of poison. Maybe it had been better for Socrates if he had had for instance Plato speak his defense. Especially if Plato had had half a contingent of armed warriors to back him up. Then what happened to them? According to the saga, Eric did not have much benefit of the poem because he died a year or so after the meeting, fighting the Irish. Reading the saga, you get the impression that the meeting in York took place one or a few years after Eric Bloodaxe left Norway. Historians place Eric's being driven out of Norway and his death at respectively around 933 and 954, thus the 21 years seem far longer than the impression you may get in the saga itself. Anyhow, Eric's sons went back to Norway and had a series of battles with Hakon Adalstenfostre. In the last battle, Hakon won but died from a battle-wound. He was succeeded by one of Eric's sons, Harald Grafeld, who later fell in a battle in Jutland. Arinbjorn who fought together with Harold Grafeld did as well and fell in the same battle. Queen Gunhild left York for Denmark and is not mentioned further in the saga. According to history she came to Norway, when her sons tried to gain power. Egil Skallagrimsson went back to Iceland. A poem had saved his life. After further traveling he stayed in Iceland, not necessarily fighting physically but remained able to engage in conflict. He grew very old according to the standard of his times. This had side effects, including him surviving two of his sons. When the last son drowned, he at the proposal of his daughter made the poem Sonartorrek (the irreparable loss of sons), which is regarded as one of the most important elements of the Germanic literature. This is, however, another aspect of the saga.

Conclusion

Signs of psychopathic behaviour is listed above where both main characters were known to cause wicked things to happen to others, and even kill fellow humans being without any remorse. The raising of a curse-pole (Nithing pole) by Egil Skallagrimsson was apparently the wizard act, resulting in captivation of Eric Bloodaxe. The authors suggest that this Old Norse act used for cursing others, can be viewed as a metaphor of what we now days call a master manipulation, but more importantly that we should remember to enjoy and value a poem. This narrative medicine of Egil Skallagrimsson gives a voice to the fact that a poem can save human life.

Funding: This study did not receive any funding or financial support.

Disclosures: The authors have no personal, financial, or institutional interest.

Acknowledgments: The authors wish to thank Dr. Ármann Jakobsson professor in Old Icelandic Literature at the Faculty of Icelandic and Comparative Cultural Studies, University of Iceland, for important guidance, and Jonah Ohayv for proofreading.

References

- World Health Organization. (1992) The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders, Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. [Ref.]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013) A.P.P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition, Washington DC and London, England (DSM-5). [Ref.]

- Miller JD, et al. (2017) Psychopathy and Machiavellianism: A Distinction Without a Difference? J Pers. 85(4): 439-453. [PubMed.]

- Douglas KS, et al. (1999) Assessing risk for violence among psychiatric patients: the HCR-20 violence risk assessment scheme and the Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version. J Consult Clin Psychol. 67(6): 917-930. [PubMed.]

- Miskovich TA, et al. (2018) Abnormal cortical gyrification in criminal psychopathy. Neuroimage Clin. 19: 876-882. [PubMed.]

- Green WC, Egil's Saga. (1893) Icelandic Saga Database, Sveinbjorn Thordarson (ed). [Ref.]

- Einarsson HB, et al. (2019) [Visna of Egill Skallagrimsson]. Laeknabladid. 105(5): 223-230. [PubMed.]

- Jakobsson A. (2017) The troll inside you: paranormal activity in the medieval north. Punctum Books. 9. [Ref.]

- Waters F, et al. (2016) What Is the Link Between Hallucinations, Dreams, and Hypnagogic-Hypnopompic Experiences? Schizophr Bull. 42(5): 1098-1109. [Ref.]