>Corresponding Author : Anubha Bajaj

>Article Type : Complimentary Article

>Volume : 2 | Issue : 1

>Received Date : 20 January, 2022

>Accepted Date : 28 January, 2022

>Published Date : 30 January, 2022

>DOI : https://doi.org/10.54289/JVVD2200103

>Citation : : Bajaj A. (2022) The Aural Defilement-Otitis Media. J Virol Viral Dis 2(1): doi https://doi.org/10.54289/JVVD2200103

>Copyright : © 2022 Bajaj A. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Complimentary Article | Open Access

Consultant Histopathologist, New Delhi, India

*Corresponding author: Anubha Bajaj, Consultant Histopathologist, New Delhi, India

Preface:

Otitis media is an infectious disease arising within the middle ear. Otitis media emerges as an acute or chronic inflammation or infection of middle ear cavity or middle ear space. The condition is preponderantly constituted of acute otitis media, chronic suppurative otitis media and otitis media with effusion. A globally discerned infection, otitis media appears due to diverse bacterial or viral agents although fungal or pneumocystis infection can exceptionally appear in immunocompromised or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected subjects.

Disease Characteristics

Although a variety of factors predispose to otitis media such as congenital palate defects, altered immunity of host, viral infection or bacterial infection, dysfunction or obstruction of the Eustachian tube appears as a significant contributory factor.

Of obscure incidence, otitis media is preponderantly discerned in children between 6 months to 24 months and disease incidence declines following 5 years of age. Nevertheless, no age of disease emergence is exempt [1,2].

Otitis media is uncommon in adults and specific subpopulations such as children with cleft palate, reoccurring otitis media or immunocompromised individuals may be incriminated. A mild male predominance is observed [1,2].

Infection of middle ear can be due to bacteria, viruses or may emerge as a coinfection. Commonly, bacterial organisms such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenza or Moraxella catarrhalis may engender otitis media. Viruses initiating otitis media are respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), coronavirus, influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, adenovirus, human meta-pneumovirus, picornaviruses, rhinovirus or adenovirus [1,2].

Majority (95%) of instances of otitis media appear due to immunodeficiency incurred with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, diabetes mellitus, diverse disorders of immunodeficiency, genetic predisposition, engendered mucins with anomalies of genetic expression especially upregulation of MUC5B, anatomic anomalies of the palate and tensor veli palatine, ciliary dysfunction, cochlear implant, deficiency of vitamin A or infection with bacterial or viral pathogens [1,2].

Otitis media is segregated into diverse subtypes contingent to pertinent clinical features as

•acute otitis media which emerges as an acute infection of middle ear. •otitis media with effusion wherein fluid accumulates within the middle ear in the absence of cogent signs or symptoms of acute infection. •adhesive otitis media demonstrates a retracted tympanic membrane. accompanied with adhesions confined to medial wall of tympanic cavity. Perforation of tympanic membrane may or may not occur [3,4].

•Chronic otitis media is associated with perforation of tympanic membrane along with reoccurring infections of the middle ear.

•Benign or inactive chronic otitis media displays a dry perforation of the tympanic membrane.

•Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) exhibits discharge of purulent material through a perforated tympanic membrane.

•Chronic otitis media with effusion, previously designated as chronic serous otitis media, exemplifies discharge of serous fluid through a perforated tympanic membrane [3,4].

•Otomastoiditis is comprised of inflammation or infection ranging from acute otitis media or chronic otitis media which disseminates and incriminates the mastoid.

Disease Pathogenesis:

Infection of middle ear as discerned with otitis media may occur following pharyngitis or through the Eustachian tube.

Factors contributing to occurrence of otitis media appear as preceding upper respiratory tract infection, male gender, obstructive adenoid hypertrophy, allergic manifestations, day care institutional assembly, absence of breastfeeding, lower socioeconomic status, exposure to environmental smoke, employment of pacifiers, immunocompromised individuals, gastroesophageal reflux disease, history of repetitive childhood otitis media and diverse genetic predisposition [3,4].

Following a pertinent viral or bacterial infection, engendered otitis media initiates an inflammation of the upper respiratory tract implicating nasopharynx, nasal mucosa, middle ear mucosa or Eustachian tubes. Anatomical space of middle ear is restricted and ensuing oedema associated with inflammation impedes the slender Eustachian tube along with reduction in ventilation [3,4].

Consequent enhancement of negative pressure within the middle ear, an elevated exudate arising from inflamed respiratory tract mucosa besides accumulated mucosal secretions permit colonization of bacterial and viral organisms within the middle ear. Microbial effervescence thus engenders suppuration and overt purulent secretions within the middle ear space. Subsequently, a bulging or erythematous tympanic membrane and purulent middle ear fluid is discernible [3,4].

In contrast, chronic serous otitis media (CSOM) represents with dense, amber-coloured fluid confined to the middle ear space and a retracted tympanic membrane upon otoscopy. Aforesaid lesions are associated with decimated mobility of the tympanic membrane, as discerned with tympanometry or pneumatic otoscopy [3,4].

Clinical Elucidation:

The condition depicts a bulging, hyperaemic or opaque tympanic membrane with restricted mobility. Purulent otorrhoea may emerge [5,6].

Pertinent clinical symptoms of otitis media appear as otalgia. Non-specific signs and symptoms emerge as pulling or tugging at the ears, irritability, headache, disturbed sleep pattern or poor-quality sleep, inadequate feeding, anorexia, vomiting or diarrhoea. Approximately two thirds (66%) of incriminated subjects represent with low grade pyrexia.

Commonly, acute otitis media manifests with otalgia, otorrhea, hearing loss, headache, pyrexia or irritability [5,6].

Otitis media with effusion appears as an asymptomatic infection. Symptomatic individuals represent with mild conductive hearing loss. Chronic otitis media may manifest persistent otorrhea and hearing loss.

Tympanosclerosis or dystrophic calcification of tympanic membrane or middle ear is associated with an estimated ~ 33% of repetitive episodes of otitis media. The condition is reversible in children although appears irreversible in adults and is accompanied with conductive hearing loss [5,6].

Severe otitis media is associated with destruction of bony ossicles of middle ear [5,6].

Histological Elucidation:

Upon gross examination, miniature fragments of soft, rubbery, grey/white granulation tissue are obtained.

Morphology of otitis media is contingent to disease severity [7,8].

Upon microscopy, acute and chronic inflammatory cells are admixed within haphazardly disseminated glands with significant glandular metaplasia and layering ciliated epithelium. Foci of fibrosis, haemorrhage, calcification or tympanosclerosis, cholesterol granulomas and reactive bone formation are discerned [7,8].

Cholesterol granuloma emerges as a granulomatous reaction with admixed foreign body giant cells and associated cholesterol crystals generated from ruptured red blood corpuscles and denatured lipid bilayer within the cell membrane. Cholesterol clefts are prominent and impede drainage or ventilation of middle ear space [7,8].

Acute purulent otitis media typically displays oedema, hyperaemia and neutrophilic infiltration of sub-epithelial zone. With commencement of inflammation, mucosal metaplasia and configuration of granulation tissue ensues. Subsequently, epithelial metaplasia from flattened cuboidal epithelium to pseudo-stratified columnar epithelium ensues within a week along with accumulation of goblet cells [7,8].

Serous acute otitis media predominantly exemplifies inflammation of the middle ear and Eustachian tube. Venous stasis or lymphatic stasis within the nasopharynx or Eustachian tube is a significant contributory factor [7,8].

Inflammatory cytokines initiate migration of plasma cells, leukocytes and macrophages towards the inflamed site. Associated epithelial metaplasia engenders pseudostratified columnar or cuboidal epithelium with accompanying basal cell hyperplasia and augmented goblet cells [7,8].

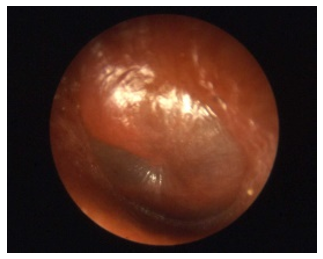

Figure 1: Otitis media acute demonstrating a bulging, erythematous tympanic membrane upon otoscopy (12).

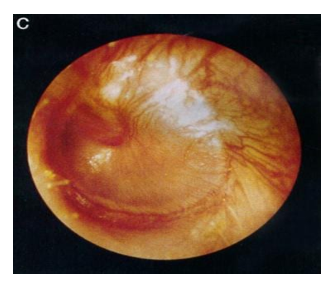

Figure 2: Otitis media acute exhibiting bulging, hyperaemic tympanic membrane with traversing congested blood vessels upon otoscopy (13).

Figure 3: Otitis media enunciating a bulging, hyperaemic tympanic membrane traversed by congested vascular articulations as discerned with otoscopy (14).

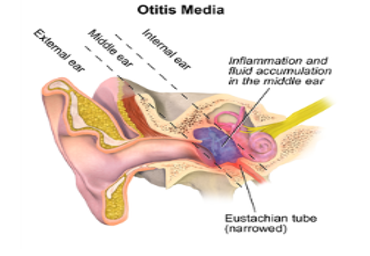

Figure 4: Otitis media exemplifying fluid accumulation within the middle ear and narrowing of the Eustachian tube (14).

Figure 5: Otitis media delineating a glistening, bulging, erythematous tympanic membrane imbued with distinctive vascular configurations (15).

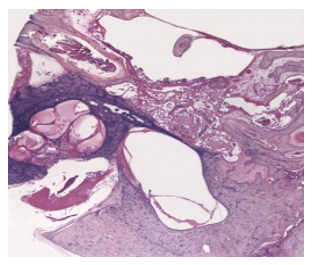

Figure 6: Chronic otitis media exhibiting an infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and macrophages incorporated within fibrotic soft tissue (16).

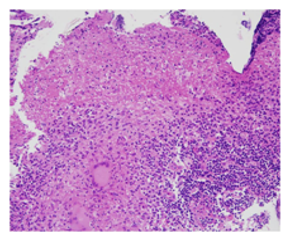

Figure 7: Tubercular otitis media enunciating a granulomatous response with epithelioid cell granulomas, langhans giant cells and foci of caseation (17).

Differential Diagnosis

Otitis media requires a segregation from diverse conditions such as

•cholesteatoma which engenders disruption and erosion of auditory ossicles, demonstrates a mass like appearance, is devoid of dependent fluid levels and may be challenging to discern where middle ear cavity exhibits diffuse opacification. Essentially, cholesteatoma is layered by keratinized, non-dysplastic, stratified squamous epithelium admixed with abundant granulation tissue and keratinous debris. The lesion is intermingled with a chronic inflammatory infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes and histiocytes. Additionally, epithelioid cell granulomas, foreign body giant cell reaction, cholesterol clefts and foci of hemosiderin pigment deposition may be exemplified [8,9].

•middle ear adenoma is composed of regularly disseminated glands which are devoid of ciliated epithelium. Tumour glands or tubules are layered with uniform, singular layer of cuboidal or columnar epithelial cells incorporated with variable quantities of eosinophilic cytoplasm and spherical to elliptical, hyperchromatic nuclei with eccentric nucleoli [8,9].

Neoplastic cells may appear plasmacytoid and demonstrate significant cellular and nuclear pleomorphism. The circumscribing stroma is sparse, fibrotic or myxoid. Mitotic activity is minimal to absent. Necrosis is absent [8,9].

•hemotympanum commonly emerges following trauma and may be associated with fracture of base of skull [8,9].

Along with, otitis media requires a demarcation from conditions such as pyrexia in infants, impaired hearing, pyrexia of unknown origin, nasal polyps, allergic rhinitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, Haemophilus influenza infection, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, pneumococcal infection, mastoiditis or bacterial meningitis in paediatric subjects, nasopharyngeal malignancy, otitis externa, infection with human parainfluenza virus (HPIV) or associated parainfluenza viruses, passive smoking, pulmonary disease, primary ciliary dyskinesia, infection with respiratory syncytial virus or rhinovirus or teething [8,9].

Investigative Assay:

Otitis mediacan be appropriately discerned by an amalgamation of comprehensive history, pertinent clinical signs and symptoms, physical examination or otoscopy [9,10].

Otitis media is preponderantly detected with cogent clinical features accompanied with definitive signs and symptoms [9,10].

Imaging or laboratory investigations are usually superfluous. Imaging studies are required for assessing intra-temporal or intracranial complications of otitis media [9,10].

Investigations for sepsis in febrile infants below <12 weeks devoid of a specific source of infection apart from acute otitis media are necessitated. Relevant systemic or congenital diseases require exclusion [9,10].

Moderate to severe bulging of tympanic membrane, contemporary otorrhoea un-associated with otitis externa or minimal bulging of tympanic membrane with accompanying recent pain within the ear or erythema is indicative of acute otitis media [9,10].

Diverse investigative modalities such as pneumatic otoscopy, tympanometry or acoustic reflectometry can be adopted to adequately diagnose otitis media [9,10].

Otoscopy is a preliminary, convenient methodology of aural examination. Acute otitis media depicts a normal or erythematous tympanic membrane with fluid accumulation within the middle ear space [9,10].

Suppurative otitis media demonstrates accumulation of purulent fluid with a visible, bulging tympanic membrane. External ear canal can be oedematous wherein significant oedema is associated with otitis externa [9,10].

Upon otoscopy, acute otitis media represents with a bulging tympanic membrane. Pneumatic otoscopy displays impaired mobility of the tympanic membrane. Erythema of tympanic membrane appears as a non-specific sign although in combination middle ear effusion, an erythematous tympanic membrane may appear diagnostic [9,10].

Upon otoscopy, chronic otitis media demonstrates a perforated tympanic membrane [9,10].

As the diagnosis of acute otitis media is contingent to precise clinical evaluation, disease assessment by imaging remains superfluous. Chronic otitis media associated with hearing loss and an indiscernible tympanic membrane may necessitate pertinent imaging. Imaging features are variable [10,11].

Upon high resolution computerized tomography (CT) of the temporal bone features such as soft tissue density within the middle ear cavity, thickened or bulging tympanic membrane or perforation of the tympanic membrane may be observed [10,11].

Chronic otitis media exemplifies effusion or air-fluid level within the middle ear, bony erosion in below < 10% instances, sclerosis of adjacent bone and hypo-pneumatisation of the mastoid [10,11].

Computerized tomography (CT) of temporal bones is beneficial in assessing complications of otitis media such as mastoiditis, epidural abscess, thrombophlebitis of the sigmoid sinus, meningitis, brain abscess, subdural abscess, ossicular disease or cholesteatoma [10,11].

Upon magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a fluid signal is observed within the middle ear cavity and mastoid antrum. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is optimal in assessing fluid collections within the middle ear [10,11].

Tympanocentesis is advantageous in evaluating fluid within the middle ear cavity wherein culture and sensitivity can be optimally employed in refractory instances. Besides, tympanometry or acoustic reflectometry may be adopted in evaluating middle ear effusion [10,11].

Therapeutic Options:

Therapy of otitis media with antibiotics remains a debatable issue and pertains to subtype of otitis media [10,11].

Treatment of acute otitis media is aimed at pain alleviation and curbing the infectious process with antibiotics. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are adopted to control pain. Individuals with suppurative acute otitis media can be administered oral antibiotics. Perforation of tympanic membrane is optimally treated with topical antibiotics [10,11].

Inadequate therapy leads to oozing of suppurative fluid from the middle ear into adjacent anatomical locations with consequent emergence of complications such as perforation of tympanic membrane, mastoiditis, labyrinthitis, petrositis, meningitis, brain abscess, hearing loss and thrombosis of lateral sinus or cavernous sinuses [10,11].

Established acute otitis media can be treated with amoxicillin and the therapy appears efficacious in children below < 2 years. Delayed therapy may be associated with accumulated fluid within the middle ear for extended duration which may impact hearing and speech besides engendering aforesaid complications [10,11].

Analgesics or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as acetaminophen may be employed singularly or in combination in order to relieve pain associated with otitis media [10,11].

Repetitive episodes of acute otitis media beyond > 4 within a duration of one year can be treated with myringotomy with placement of a tube or grommet. Repetitive infections subjected to antibiotic therapy are indicative of Eustachian tube dysfunction. Insertion of tympanostomy tube permits ventilation of middle ear space and conserves normal hearing. Otitis media acquired with tube placement is treated with topical antibiotics [10,11].

Reoccurring acute otitis media mandates preliminary, aggressive therapeutic intervention [10,11].

Complications associated with otitis media appear as intra-temporal complications such as conductive or sensorineural hearing loss, acute or chronic perforation of the tympanic membrane, chronic suppurative otitis media, cholesteatoma, tympanosclerosis, mastoiditis, petrositis, labyrinthitis, facial paralysis, cholesterol granuloma or infectious eczematoid dermatitis [10,11].

Intracranial complications emerge as meningitis, subdural empyema, brain abscess, extradural abscess, lateral sinus thrombosis or otitic hydrocephalus. Complications associated with otitis media are challenging to treat [10,11].

Majority of subjects with otitis media are associated with a superior prognosis. With the advent of contemporary antibiotics, mortality due to acute otitis media is exceptional. Preliminary disease discernment and cogent therapy is advantageous in controlling the infection. Efficacious antibiotics are the prime therapeutic strategy [10,11].

Prognostic factors influencing disease outcomes are

•paediatric subjects manifesting below < three episodes of acute otitis media.

•paediatric subjects with diverse, challenging to treat complications and enhanced possible disease reoccurrence. Although exceptional, intra-temporal and intracranial complications are associated with significant mortality.

•paediatric subjects with preceding pre-lingual otitis media exhibit mild or moderate conductive hearing loss.

•paediatric subjects with otitis media emerging within 2 years are unable to appropriately perceive strident or high-frequency consonants, such as sibilants [10,11].

References:

- Danishyar A, Ashurst JV. (2021) “Acute Otitis Media” Stat Pearls International. Treasure Island. Florida. [Ref.]

- Meherali S, Campbell A, et al. (2019) “Understanding Parents Experiences and Information Needs on Paediatric Acute Otitis Media: A Qualitative Study” J Patient Exp. 6(1): 53-61. [PubMed.]

- Protasova IN, Peryanova OV, et al. (2017) “Acute otitis media in the children: aetiology and the problems of antibacterial therapy” Vestn Otorinolaringol. 82(2): 84-89. [PubMed.]

- Mittal R, Robalino G, et al. (2014) Immunity genes and susceptibility to otitis media: a comprehensive review” J Genet Genomics. 41(11): 567-581. [PubMed.]

- Seppälä E, Sillanpää S, et al. (2016) Human enterovirus and rhinovirus infections are associated with otitis media in a prospective birth cohort study. J Clin Virol. 85: 1-6. [PubMed.]

- Vila PM, Ghogomu NT, et al. (2017) Infectious complications of paediatric cochlear implants are highly influenced by otitis media. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 97: 76-82. [PubMed.]

- Usonis V, Jackowska T, et al. (2016) Incidence of acute otitis media in children below 6 years of age seen in medical practices in five East European countries” BMC Pediatr. 26: 16-108. [PubMed.]

- Schilder AG, Chonmaitree T, et al. (2016) Otitis media” Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2(1): 16063. [PubMed.]

- Siddiq S, Grainger J. (2015) The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media: American Academy of Paediatrics Guidelines 2013 Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 100(4):193-197. [PubMed.]

- Brinker DL, MacGeorge E, et al. (2019) “Diagnostic Accuracy, Prescription Behaviour and Watchful Waiting- Efficacy for Paediatric Acute Otitis Media” Clin Pediatr (Phila). 58(1): 60-65. [PubMed.]

- Voitl P, Meyer R, et al. (2019) Occurrence of patients compared in a paediatric practice and paediatric hospital outpatient clinic” J Child Health Care. 23(4): 512-521. [PubMed.]

- Image 1 Courtesy: Stat pearls.com. [Ref.]

- Image 2 Courtesy: Medscape reference. [Ref.]

- Image 3 and 4 Courtesy: Wikipedia. [Ref.]

- Image 5 Courtesy: MDEdge.com. [Ref.]

- Image 6 Courtesy: Entokey.com. [Ref.]

- Image 7 Courtesy: Medcrave International. [Ref.]